p. 473

of the people, but over the most accomplished men, over men in all stations, of all nations, of all religions; to reign over them without any exterior constraint, to keep them united by durable bonds, to inspire them all with one spirit; to govern with all possible precision, activity, and silence, men spread over the whole surface of the globe, even to its utmost confines. This is a problem which no political wisdom has ever been able to solve. To reunite the distinctions of Equality, Despotism, and Liberty; to prevent the treasons and persecutions which would be the inevitable consequences; of nothing, to create great things; to stand firm against the swelling torrent of evils and abuse; to make happiness universally shine on human nature; would be a master-piece of morality and polity re-united. The civil constitutions of states offer but little aid to such an undertaking. Fear and violence are their grand engines; with us, each one is voluntarily to lend his assistance. . . . Were men what they ought to be, we might on their first admission into our society explain the greatness of our plans to them; but the lure of a secret is perhaps the only means of retaining those who might turn their backs upon us as soon as their curiosity had been gratified: The ignorance or imperfect education of many makes it requisite that they should be first formed by our moral lessons. The complaints, the murmurs of others against the trials to which we are obliged to condemn them, sufficiently show you what pains we must bestow, with what patience and what constancy we must be endowed; how intensely the love of the grand object must glow in our hearts, to make us keep true to our posts in the midst of such unthankful labour; and not abandon for ever the hope of regenerating mankind.”

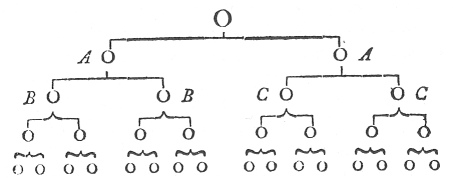

“It is to partake with us of these labours that you have been called. To observe others day and night; to form them, to succour them, to watch over them; to stimulate the courage of the pusillanimous, the activity and the zeal of the lukewarm; to instruct the ignorant; to raise up those who have fallen, to fortify those who stagger; to repress the ardour of rashness, to prevent disunion; to veil the faults and weaknesses of others; to guard against the acute inquisitiveness of wit; to prevent imprudence and treason; in short, to maintain the subordination to and esteem of our Superiors, and friendship and union among the Brethren, are the duties, among others still greater, that we impose upon you.”

“Have you any idea of secret societies; of the rank they hold, or of the parts they perform in the events of this world? Do you view them as insignificant or transient meteors? O, Brother! God and Nature, when disposing of all things according to the proper times and places, had their admirable ends in view; and they make use of these secret societies as the only and as the indispensable means of conducting us thither.”

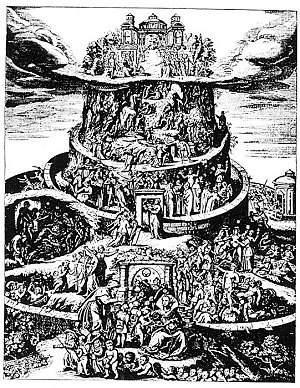

“Hearken, and may you be filled with admiration! This is the point whither all the moral tends; it is on this that depends the knowledge of the rights of secret societies, of all our doctrine, of all our ideas of good and bad, of just and unjust. You are here situated between the world past and the world to come. Cast your eyes boldly on what has passed, and in an instant ten

p. 474

thousand bolts shall fall, and thousands of gates shall burst open to futurity—You shall behold the inexhaustible riches of God and of Nature, the degradation and the dignity of man. You shall see the world and human nature in its youth, if not in its childhood, even there where you thought to find it in its decrepitude and verging toward its ruin and ignominy.”

Should this long exordium, which I have nevertheless abridged, have fatigued the reader, let him rest and reflect for an instant. The enthusiastic strain which predominates in this first part pervades the whole. Weishaupt thought it necessary to his object to afford his proselytes no time for reflection. He begins by inflaming them; he promises great things; though this impious and artful mountebank knows that he is going to fob them off with the greatest follies, the grossest impieties and errors. I have called him an impious and artful mountebank; but that is falling far short of what the proofs attest. Weishaupt knows that he deceives, and wishes to delude his proselytes in the most atrocious manner. When he has misled, he scoffs at them, and with his confidants derides their imbecility. He has, however, his reasons for beguiling them, and knows for what uses he intends them when he has infused into them his erroneous and vicious principles. The greater the consideration they may enjoy in the world, the more heartily he laughs at their delusion. He thus writes to his intimate friends: “You cannot conceive how much my degree of Priest is admired by our people. But what is the most extraordinary is, that several great protestant and reformed divines, who are of our Order, really believe that that part of the discourse which alludes to religion contains the true spirit and real sense of Christianity; poor mortals! what could I not make you believe?—Candidly I own to you, that I never thought of becoming the founder of a religion.” 8 In this manner does the impostor delude his followers, and then scoffs at them in private. These great divines were probably of that class among the protestants which we should, among us, call apostates, a Syeyes or an Autun, for example; for it is impossible that any man endowed with common sense or candour could avoid seeing that the whole tendency of this long discourse is the total overthrow of all religion and of all government.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.