p. 129

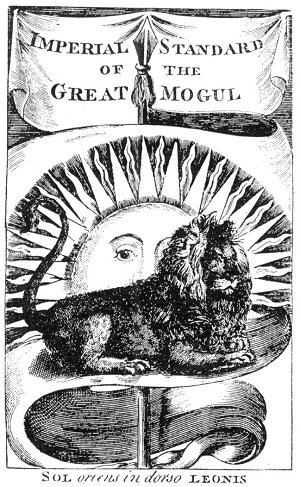

OPINIONS of authorities differ widely concerning the origin of playing cards, the purpose for which they were intended, and the time of their introduction into Europe. In his Researches into the History of Playing Cards, Samuel Weller Singer advances the opinion that cards reached Southern Europe from India by way of Arabia. It is probable that the Tarot cards were part of the magical and philosophical lore secured by the Knights Templars from the Saracens or one of the mystical sects then flourishing in Syria. Returning to Europe, the Templars, to avoid persecution, concealed the arcane meaning of the symbols by introducing the leaves of their magical book ostensibly as a device for amusement and gambling. In support of this contention, Mrs. John King Van Rensselaer states:

“That cards were brought by the home-returning warriors, who imported many of the newly acquired customs and habits of the Orient to their own countries, seems to be a well-established fact; and it does not contradict the statement made by some writers who declared that the gypsies–who about that time began to wander over Europe–brought with them and introduced cards, which they used, as they do at the present day, for divining the future.” (See The Devil’s Picture Books.)

Through the Gypsies the Tarot cards may be traced back to the religious symbolism of the ancient Egyptians. In his remarkable work, The Gypsies, Samuel Roberts presents ample proof of their Egyptian origin. In one place he writes: “When Gypsies originally arrived in England is very uncertain. They are first noticed in our laws, by several statutes against them in the reign of Henry VIII.; in which they are described as ‘an outlandish people, calling themselves Egyptians,–who do not profess any craft or trade, but go about in great numbers, * * *.'” A curious legend relates that after the destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria, the large body of attendant priests banded themselves together to preserve the secrets of the rites of Serapis. Their descendants (Gypsies) carrying with them the most precious of the volumes saved from the burning library–the Book of Enoch, or Thoth (the Tarot)–became wanderers upon the face of the earth, remaining a people apart with an ancient language and a birthright of magic and mystery.

Court de Gébelin believed the word Tarot itself to be derived from two Egyptian words, Tar, meaning “road,” and Ro, meaning “royal.” Thus the Tarot constitutes the royal road to wisdom. (See Le Monde Primitif.) In his History of Magic, P. Christian, the mouthpiece of a certain French secret society, presents a fantastic account of a purported initiation into the Egyptian Mysteries wherein the 22 major Tarots assume the proportions of trestleboards of immense size and line a great gallery. Stopping before each card in turn, the initiator described its symbolism to the candidate. Edouard Schuré, whose source of information was similar to that of Christian’s, hints at the same ceremony in his chapter on initiation into the Hermetic Mysteries. (See The Great Initiates.) While the Egyptians may well have employed the Tarot cards in their rituals, these French mystics present no evidence other than their own assertions to support this theory. The validity also of the so-called Egyptian Tarots now in circulation has never been satisfactorily established. The drawings are not only quite modem but the symbolism itself savors of French rather than Egyptian influence.

The Tarot is undoubtedly a vital element in Rosicrucian symbolism, possibly the very book of universal knowledge which the members of the order claimed to possess. The Rota Mundi is a term frequently occurring in the early manifestoes of the Fraternity of the Rose Cross. The word Rota by a rearrangement of its letters becomes Taro, the ancient name of these mysterious cards. W. F. C. Wigston has discovered evidence that Sir Francis Bacon employed the Tarot symbolism in his ciphers. The numbers 21, 56, and 78, which are all directly related to the divisions of the Tarot deck, are frequently involved in Bacon’s cryptograms. In the great Shakespearian Folio of 1623 the Christian name of Lord Bacon appears 21 times on page 56 of the Histories. (See The Columbus of Literature.)

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.