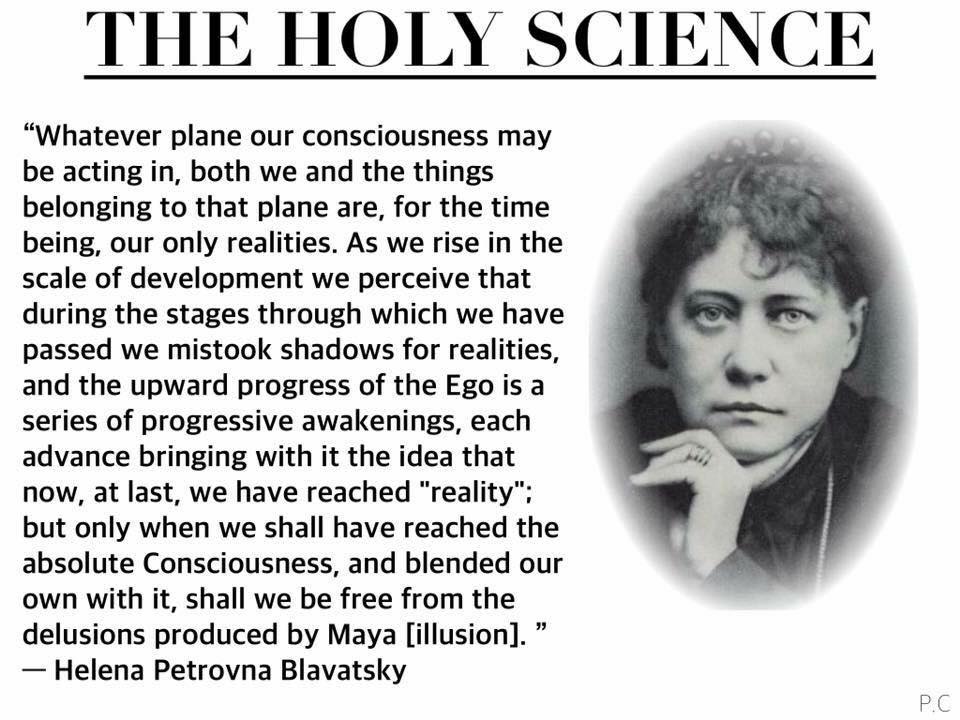

Madame Helena Blavatsky had considered the ancient Gnostics her kindred spirits. She wrote about  them often in the best of light in her lengthy occult masterpieces. The Gnosis, which H. P. Blavatsky called “an echo of our archaic doctrine” and Pythagoras “the knowledge of things as they are.”

them often in the best of light in her lengthy occult masterpieces. The Gnosis, which H. P. Blavatsky called “an echo of our archaic doctrine” and Pythagoras “the knowledge of things as they are.”

“My doctrine is not mine, but Theirs who sent me,” she said, and every Teacher of Truth has said the same. It is one of the great texts of the Christian religion interpreted in different ages, however, in very different ways. We find one of the Christian Fathers, Clemens Alexandrinus, defining the “Gnostic,” or one who possessed this ancestral Theosophy or Gnosis, as “the enlightened or perfect Christian.”

In the nineteenth century Blavatsky had brought to the world a new form of the ancient religion of the Gnostics in what is called Theosophy. In fact, like me, Blavatsky had claimed that from the once universal religion of Gnosticism, would spring the various religions such as Buddhism, Brahmanism, and early Christianity.

Blavatsky has much to say about the ancient Gnostics and Gnosis in Isis Unveiled. Here is a small sample of her writings.

The foregoing is from the description given by Theodoret and adopted by King in his Gnostics, with additions from Epiphanius and Irenaeus. But the former gives a very imperfect version, concocted partly from the descriptions of Irenaeus, and partly from his own knowledge of the later Ophites, who, toward the end of the third century, had blended already with several other sects. Irenaeus also confounds these sects very frequently, and the real theogony of the Ophites is given by none of

them correctly. With the exception of a change in names, the above-given theogony is that of all the Gnostics, and also of the Nazarenes.

Ophis is but the successor of the Egyptian Chnuphis (Khnemu), the Good Serpent with a lion’s radiating head, and was held from days of the highest antiquity as an emblem of wisdom, or Thoth, the instructor and Savior of humanity, the ‘Son of God.’ “Oh men, live soberly . . . win your immortality!” exclaims Hermes, the thrice-great Trismegistus. “Instructor and guide of humanity, I will lead you on to salvation.”

Thus the oldest sectarians regarded Ophis, the Agathodaimon, as identical with Christos; the serpent being the emblem of celestial wisdom and eternity, and, in the present case, the antitype of the Egyptian Chnuphis-serpent. These Gnostics, the earliest of our Christian era, held: “That the supreme Aeon, having emitted other Aeons out of himself, one of them, a female, Prunikos (concupiscence), descended into the chaos, whence, unable to escape, she remained suspended in the mid-space, being too clogged by matter to return above, and not falling lower where there was nothing in affinity with her nature. She then produced her son Ilda-Baoth, the God of the Jews, who, in his turn, produced seven Aeons, or angels, who created the seven heavens.”

In this plurality of heavens the Christians believed from the first, for we find Paul teaching of their existence, and speaking of a man “caught up to the third heaven” {2 Cor., xii, 2). “From these seven angels Ilda-Baoth shut up all that was above him, lest they should know of anything superior to himself. They then created man in the image of their Father, but prone and crawling on the earth like a worm. But the heavenly mother, Prunikos, wishing to deprive Ilda-Baoth of the power with which she had unwittingly endowed him, infused into man a celestial spark — the spirit.

Immediately man rose upon his feet, soared in mind beyond the limits of the seven spheres, and glorified the Supreme Father, Him that is above Ilda-Baoth. Hence the latter, full of jealousy, cast down his eyes upon the lowest stratum of matter, and begot a potency in the form of a serpent, whom they [Ophites] call his son. Eve, obeying him as the son of God, was persuaded to eat of the Tree of Knowledge.”

It is a self-evident fact that the serpent of the Genesis, who appears suddenly and without any preliminary introduction, must have been the antitype of the Persian Arch-Devs, whose head is Ashmog, the “two footed serpent of lies.” If the serpent had been deprived of his limbs before he had tempted woman unto sin, why should God specify as a punishment that he should go “upon his belly”? Nobody supposes that he walked upon the extremity of his tail.

This controversy about the supremacy of Jehovah, between the Presbyters and Fathers on the one hand, and the Gnostics, the Nazarenes, and all the sects declared (as a last resort) heterodox on the other, lasted till the days of Constantine and later. That the peculiar ideas of the Gnostics about the genealogy of Jehovah, or the proper place that had to be assigned, in the Christian-Gnostic Pantheon, to the God of the Jews, were at first deemed neither blasphemous nor heterodox, is evident in the difference of opinions held on this question by Clement of Alexandria, for instance, and Tertullian.

The former, who seems to have known Basilides better than anybody else, saw nothing heterodox or blamable in the mystical and transcendental views of the new Reformer. “In his eyes,” remarks the author of The Gnostics, speaking of Clement, “Basilides was not a heretic, i. e., an innovator as regards the doctrines of the Christian Church, but a mere theosophic philosopher, who sought to express ancient truths under new forms, and perhaps to combine them with the new faith, the truth of which he could admit without necessarily renouncing the old, exactly as is the case with the learned Hindus of our day.”

Not so with Irenaeus and Tertullian. The principal works of the latter against the Heretics were written after his separation from the Catholic Church, when he had ranged himself among the zealous followers of Montanus; they teem with unfairness and bigoted prejudice.

He has exaggerated every Gnostic opinion into a monstrous absurdity, and his arguments are not based on coercive reasoning but simply on the blind stubbornness of a partisan fanatic. Discussing Basilides, the “pious, god-like, theosophic philosopher,” as Clement of Alexandria thought him, Tertullian exclaims: “After this Basilides, the heretic, broke loose. He asserted that there is a Supreme God, by name Abraxas, by whom Mind was created, whom the Greeks call Nous.

From her emanated the Word; from the Word, Providence; from Providence, Virtue and Wisdom; from these two again, Principalities, Powers and Angels were made; thence infinite productions and emissions of angels. . . . Among the lowest angels, indeed, and those that made this world, he sets last of all the god of the Jews, whom he denies to be God himself, affirming that he is but one of the angels.”

SOURCE: Isis Unveiled: a Master Key to the Mysteries of Ancient …, Volume 2, Part 1 By Helena Petrovna Blavatsky – Page 188

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.