p. 121

foolish and perhaps worse actions of ours, any one of which, done by another, would be enough, with us, to destroy his reputation.

If we think the people wise and sagacious, and just and appreciative, when they praise and make idols of us, let us not call them unlearned and ignorant, and ill and stupid judges, when our neighbor is cried up by public fame and popular noises.

Every man hath in his own life sins enough, in his own mind trouble enough, in his own fortunes evil enough, and in performance of his offices failings more than enough, to entertain his own inquiry; so that curiosity after the affairs of others cannot be without envy and an ill mind. The generous man will be solicitous and inquisitive into the beauty and order of a well-governed family, and after the virtues of an excellent person; but anything for which men keep locks and bars, or that blushes to see the light, or that is either shameful in manner or private in nature, this thing will not be his care and business.

It should be objection sufficient to exclude any man from the society of Masons, that he is not disinterested and generous, both in his acts, and in his opinions of men, and his constructions of their conduct. He who is selfish and grasping, or censorious and ungenerous, will not long remain within the strict limits of honesty and truth, but will shortly commit injustice. He who loves himself too much must needs love others too little; and he who habitually gives harsh judgment will not long delay to give unjust judgment.

The generous man is not careful to return no more than he receives; but prefers that the balances upon the ledgers of benefits shall be in his favor. He who hath received pay in full for all the benefits and favors that he has conferred, is like a spendthrift who has consumed his whole estate, and laments over an empty exchequer. He who requites my favors with ingratitude adds to, instead of diminishing, my wealth; and he who cannot return a favor is equally poor, whether his inability arises from poverty of spirit, sordidness of soul, or pecuniary indigence.

If he is wealthy who hath large sums invested, and the mass of whose fortune consists in obligations that bind other men to pay him money, he is still more so to whom many owe large returns of kindnesses and favors. Beyond a moderate sum each year, the wealthy man merely invests his means: and that which he never

p. 122

uses is still like favors unreturned and kindnesses unreciprocated, an actual and real portion of his fortune.

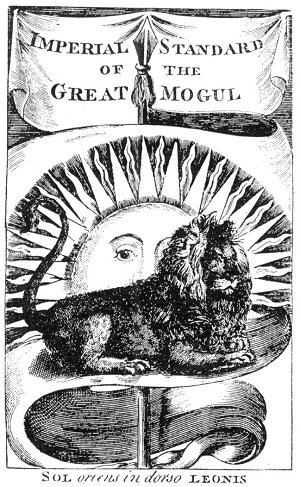

Generosity and a liberal spirit make men to be humane and genial, open-hearted, frank, and sincere, earnest to do good, easy and contented, and well-wishers of mankind. They protect the feeble against the strong, and the defenceless against rapacity and craft. They succor and comfort the poor, and are the guardians, under God, of his innocent and helpless wards. They value friends more than riches or fame, and gratitude more than money or power. They are noble by God’s patent, and their escutcheons and quarterings are to be found in heaven’s great book of heraldry. Nor can any man any more be a Mason than he can be a gentle-man, unless he is generous, liberal, and disinterested. To be liberal, but only of that which is our own; to be generous, but only when we have first been just; to give, when to give deprives us of a luxury or a comfort, this is Masonry indeed.

He who is worldly, covetous, or sensual must change before he can be a good Mason. If we are governed by inclination and not by duty; if we are unkind, severe, censorious, or injurious, in the relations or intercourse of life; if we are unfaithful parents or undutiful children; if we are harsh masters or faithless servants; if we are treacherous friends or bad neighbors or bitter competitors or corrupt unprincipled politicians or overreaching dealers in business, we are wandering at a great distance from the true Masonic light.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.