“The King Angashuna caused the betrothal of his daughter, the beautiful Kalavatti, with the young son of Vamadeva, the powerful King of Antarvedi, named Govinda, to be celebrated with great pomp.

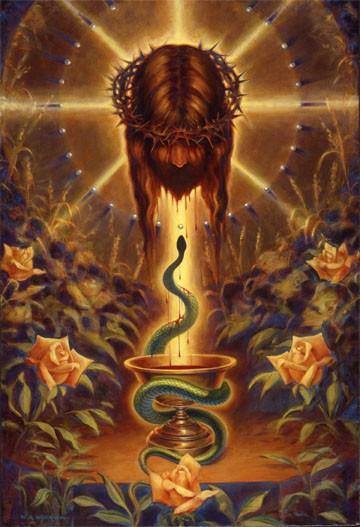

“But as Kalavatti was amusing herself in the groves with her companions, she was stung by a serpent and died. Angashuna tore his clothes, covered himself with ashes, and cursed the day when he was born.

“Suddenly, a great rumor spread through the palace, and the following cries were heard, a thousand times repeated: ‘Pacya pitaram; pacya gurum!’ ‘The Father, the Master!’ Then Christna approached, smiling, leaning on the arm of Ardjuna. . . . ‘Master!’ cried Angashuna, casting himself at his feet, and sprinkling them with his tears, ‘See my poor daughter!’ and he showed him the body of Kalavatti, stretched upon a mat. . . .

” ‘Why do you weep?’ replied Christna, in a gentle voice. ‘Do you not see that she is sleeping? Listen to the sound of her breathing, like the sigh of the night wind which rustles the leaves of the trees. See, her cheeks resuming their color, her eyes, whose lids tremble as if they were about to open; her lips quiver as if about to speak; she is sleeping, I tell you; and hold! see, she moves, Kalavatti! Rise and walk!’

“Hardly had Christna spoken, when the breathing, warmth, movement, and life returned little by little, into the corpse, and the young girl, obeying the injunction of the demi-god, rose from her couch and

Page 242

rejoined her companions. But the crowd marvelled and cried out: ‘This is a god, since death is no more for him than sleep!’ ”

All such parables are enforced upon Christians, with the addition of dogmas which, in their extraordinary character, leave far behind them the wildest conceptions of heathenism. The Christians, in order to believe in a Deity, have found it necessary to kill their God, that they themselves should live!

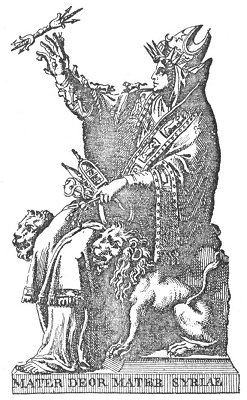

And now, the Supreme, unknown one, the Father of grace and mercy, and his celestial hierarchy are managed by the Church as though they were so many theatrical stars and supernumeraries under salary! Six centuries before the Christian era, Xenophanes had disposed of such anthropomorphism by an immortal satire, recorded and preserved by Clement of Alexandria.

“There is one God Supreme. . . . . . . . .

Whose form is not like unto man’s, and as unlike his nature;

But vain mortals imagine that gods like themselves are begotten

With human sensations, and voice, and corporeal members;

So if oxen or lions had hands and could work in man’s fashion

And trace out with chisel or brush their conception of Godhead

Then would horses depict gods like horses, and oxen like oxen,

Each kind the Divine with its own form and nature endowing.”

And hear Vyasa — the poet-pantheist of India, who, for all the scientists can prove, may have lived, as Jacolliot has it, some fifteen thousand years ago — discoursing on Maya, the illusion of the senses:

“All religious dogmas only serve to obscure the intelligence of man. . . . Worship of divinities, under the allegories of which, is hidden respect for natural laws, drives away truth to the profit of the basest superstitions” (Vyasa Maya).

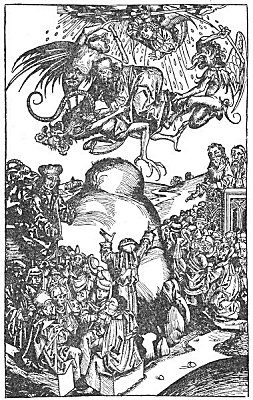

It was given to Christianity to paint us God Almighty after the model of the kabalistic abstraction of the “Ancient of Days.” From old frescos on cathedral ceilings; Catholic missals, and other icons and images, we now find him depicted by the poetic brush of Gustave Dore. The awful, unknown majesty of Him, whom no “heathen” dared to reproduce in concrete form, is figuring in our own century in Dore’s Illustrated Bible. Treading upon clouds that float in mid-air, darkness and chaos behind him and the world beneath his feet, a majestic old man stands, his left hand gathering his flowing robes about him, and his right raised in the gesture of command. He has spoken the Word, and

Page 243

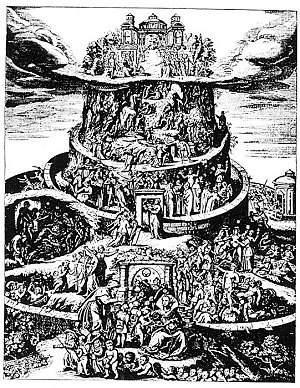

from his towering person streams an effulgence of Light — the Shekinah. As a poetic conception, the composition does honor to the artist, but does it honor God? Better, the chaos behind Him, than the figure itself; for there, at least, we have a solemn mystery. For our part, we prefer the silence of the ancient heathens. With such a gross, anthropomorphic, and, as we conceive, blasphemous representation of the First Cause, who can feel surprised at any iconographic extravagance in the representation of the Christian Christ, the apostles, and the putative Saints? With the Catholics St. Peter becomes quite naturally the janitor of Heaven, and sits at the door of the celestial kingdom — a ticket-taker to the Trinity!

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.