In Phaedrus (370 BCE), Plato details a discussion between Socrates and Phaedrus about the Egyptian myth of Thoth (Theuth), the god of the underworld who is credited with “number and calculation, geometry and astronomy, as well as the games of draughts and dice, and above all else, writing” (Phaedrus, 274d).

Now the king of all Egypt at that time was Thamus, who lived in the great city of the upper region, which the Greeks call the Egyptian Thebes, and they call the god himself Ammon. To him came Thoth to show his inventions, saying that they ought to be imparted to the other Egyptians.

Thamus, the King of the great city of the upper region, which the Greeks call the Egyptian Thebes, and they call the god himself Ammon. He had visited Thoth pleading with him to disseminate the various learning arts around Egypt. As Thoth made his presentations, Thamus would either praise or offer his criticisms.

When it came to the art of writing, Thoth told the King:

“O King, here is something that, once learned, will make the Egyptians wiser and will improve their memory; I have discovered an elixir for memory and for wisdom.” (Phaedrus, 274e)

Thoth claims that writing will allow humans to record and then recall their thoughts and thus help with their memories, but Thamus disagrees. The King believes Thoth’s love of writing had kept him from acknowledging the truth that writing would increase forgetfulness rather than improve memory.

Instead of understanding and experiencing things to create experiential knowledge, people would instead rely on reading and writing to learn a subject. In doing so, students would learn a great many subjects without properly thinking about them.

Hence, they may have the “appearance of wisdom” but “for the most part they will know nothing” (Phaedrus, 275a-b).

Thamus said;

“Most ingenious Thoth, one man has the ability to beget arts, but the ability to judge of their usefulness or harmfulness to their users belongs to another; and now you, who are the father of letters, have been led by your affection to ascribe to them a power the opposite of that which they really possess.

“For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them.

You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise.”

Socrates emphasizes this point by stating that writing alone has no understanding of itself and “continues to signify just the same thing forever” (Phaedrus, 275d-e). He instead favored discourse and conversation in the form of discourse and dialect.

What Socrates means by this is that a true philosopher’s knowledge and ideas are not to be set in stone as rigid dogmas that cannot be modified or changed with the introduction of new or contradicting information.

They must always be open to viewing issues from multiple perspectives and to arrive at the most reasonable conclusion based on truth rather than selfish motives or egotistical aims.

For Socrates, true knowledge was like the seed of a flower that continues to grow allowing for more information to be added or discarded.

By continuing a dialect and discourse with the original planters, i.e., adding new knowledge about a subject or philosophy, it becomes more beautiful and perfect and thus continues to grow becoming immortal.

Socrates had said:

“The dialectician chooses a proper soul and plants and sows within it discourse accompanied by knowledge—discourse capable of helping itself as well as the man who planted it, which is not barren but produces a seed from which more discourse grows. Such discourse makes the seed forever immortal and renders the man who has it as happy as any human being can be.” (277a)

When we study the dialectical method, we find that this can be applied to the discourse a philosopher or researcher must partake in to find truth.

This can happen in different eras or thousands of years apart between the originator of the idea or philosophy and two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to hash out the difference of opinions or facts using a scientific method of logic and reason to establish the ultimate truth.

A thinking layer of knowledge and information that is introduced into human civilization as an idea that becomes our programming code based upon how many people accept, propagate, dialect, discourse, and expand upon the idea to the point it forms our reality.

This explanation of how ideas and knowledge become immortal is how I contend that the Noosphere or World Soul is formed.

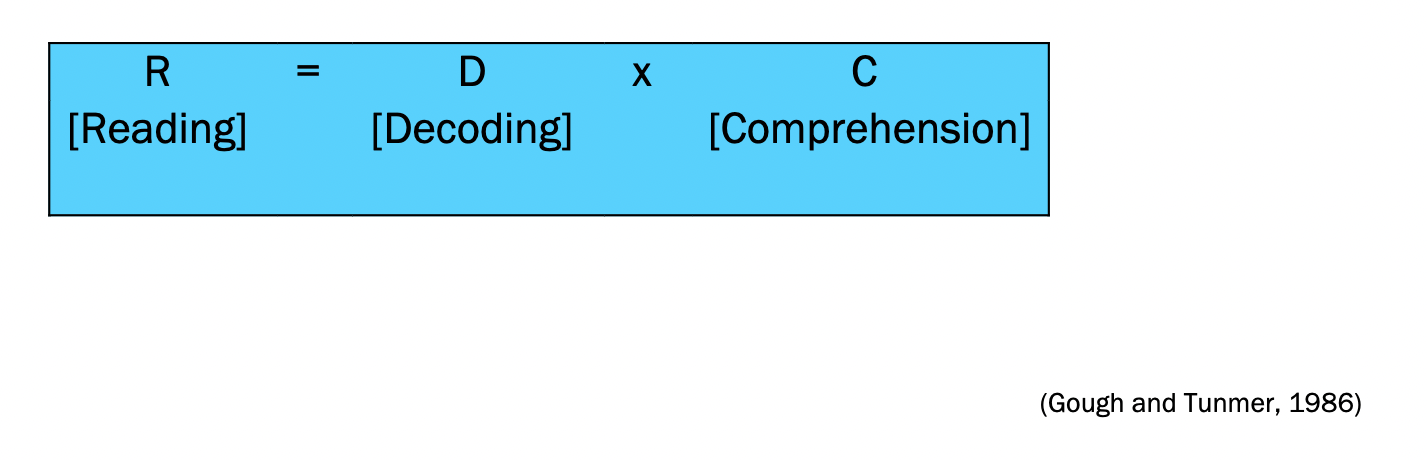

This debate that Plato puts forth between Thoth and the King of Egypt is fascinating because if we fast forward to our modern era, a 1986 study had shown that the most successful readers must first decode what they read to truly comprehend the subject.

It is called the theory of the Simple View of Reading, which defines the skills that contribute to an individual’s reading comprehension as the product of their decoding skill and language comprehension (Gough & Tunmer,1986).

Meaning, that in order to learn and know a certain subject, you cannot just tread something, you must learn to recognize and interpret information to discover the underlying meaning and to explain it in a comprehensible form.

Meaning that reading and memorizing will not equate to true understanding and wisdom.

A person must think deeply about what they read in order to understand.

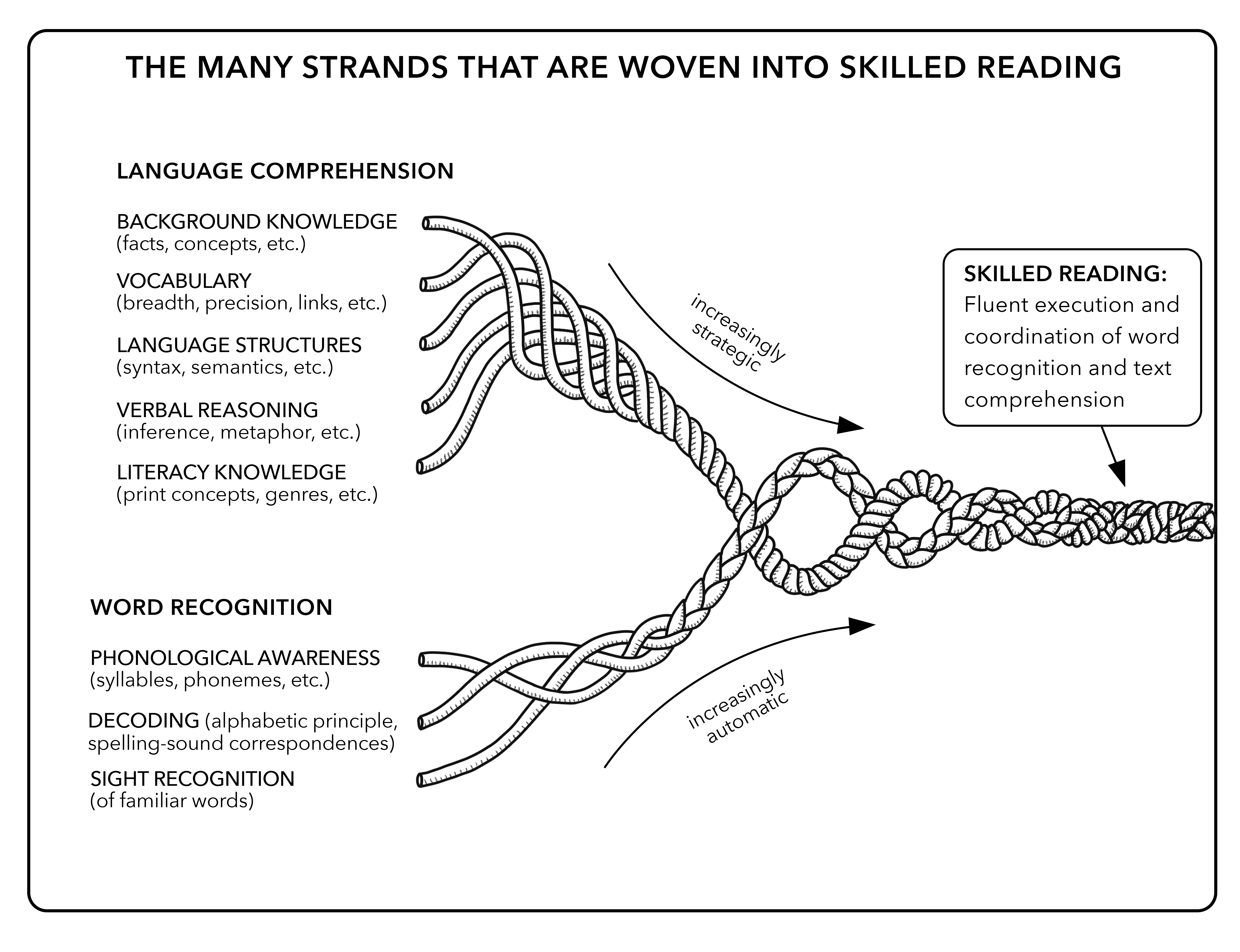

Almost two decades later, a new improved theory was put forth that had shown that there are many more skills a person must have to truly decode information and to be called an accurate researcher and or expert on any given subject.

In 2001, Dr. Hollis Scarborough, a psychologist, advanced this theory further by showing that true understanding, skill, and wisdom are attained through several different skill sets that must be used for the decoding and comprehension of knowledge and word recognition.

She used a “reading rope” model depicting a rope with its different strands to demonstrate the skills a reader needs to come to a true understanding or wisdom on a subject.

The strands of the rope show the different elements of language necessary for true comprehension (the top five strands), which bind to the three essential skills (the bottom three strands) of word recognition to form a strong rope.

If one strand is weak or if the strands are not interwoven tightly in increasingly strategic and automatic ways, then the reader cannot truly become wise.

The lower strands include:

Phonological awareness

Decoding

Alphabetic principle

Letter-sound correspondences

Sight recognition

The upper strands include:

Background knowledge

Vocabulary

Language structures

Verbal reasoning

Literacy knowledge

Therefore, attaining knowledge and becoming wise does not just involve reading about a subject, it also entails intensive thought processes from different points of view and through our own experiences, and our own capacities.

It is the quality of our thoughts in combination of who you are, what we read, and converting this knowledge (information, facts, associations etc. ) to wisdom (outcomes, philosophies etc.) is how someone truly becomes wise.

But we must remain humble in our ways and cannot become a know it all or the guru who ignorantly thinks he as all the answers. As Socrates once said:

“The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.”

A true philosopher must also always be open to discourse and dialect with other people and researchers who many will have different ideas and opinions if we truly want to arrive at truth.

Otherwise, we are living on the fumes from the bowels of the dogmatic lies written and read by mortal automatons hell bent on storming heaven to invert and control reality for their selfish gain.

SOURCES:

Phaedrus

Gough, Philip B., and William E. Tunmer. “Decoding, Readability, and Reading Disability.” Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), Jan/Feb 1986, pp. 6–10.

Scarborough, Hollis S. “Connecting Early Language and Literacy to Later Reading (Dis)Abilities: Evidence, Theory, and Practice.” Handbook of Early Literacy Research, edited by Susan B. Neuman and David K. Dickinson, Guilford Press, 2001, pp. 97–110.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

![How the holy man, Egbert, would have gone into Germany to preach, but could not; and how Wictbert went, but because he availed nothing, returned into Ireland, whence he came [Circ. 688 A.D.] | Book 5 | Chapter 8 How the holy man, Egbert, would have gone into Germany to preach, but could not; and how Wictbert went, but because he availed nothing, returned into Ireland, whence he came [Circ. 688 A.D.] | Book 5 | Chapter 8](https://www.gnosticwarrior.com/wp-content/plugins/contextual-related-posts/default.png)