The essay published in French by Alexandre Lenoir in 1809, while curious and original, contains little real information on the Tablet, which the author seeks to prove was an Egyptian calendar or astrological chart. As both Montfaucon and Lenoir–in fact all writers on the subject since 1651–either have based their work upon that of Kircher or have been influenced considerably by him, a careful translation has been made of the latter’s original article (eighty pages of seventeenth century Latin). The double-page plate at the beginning of this chapter is a faithful reproduction made by Kircher from the engraving in the Museum of Hieroglyphics. The small letters and numbers used to designate the figures were added by him to clarify his commentary and will be used for the same purpose in this work.

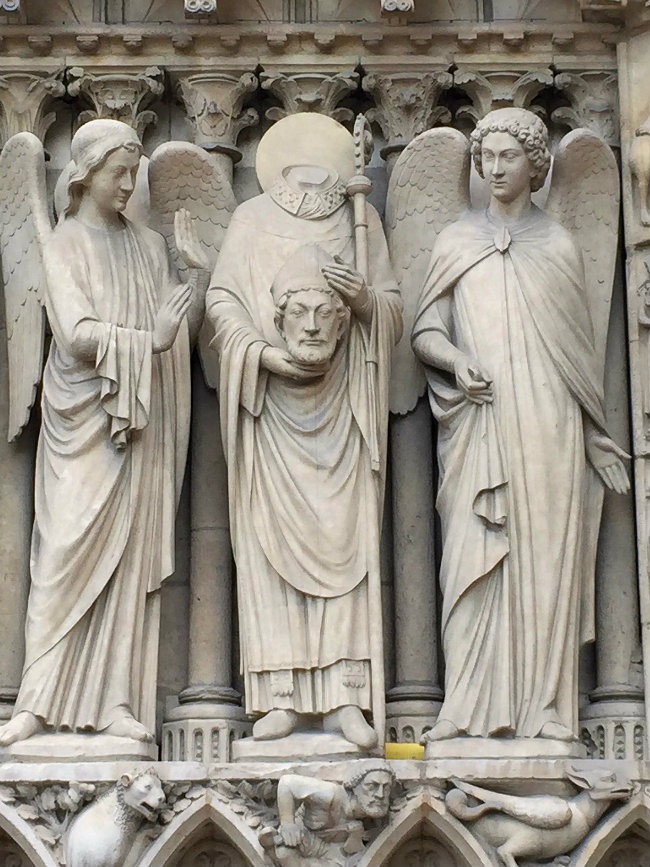

Like nearly all religious and philosophical antiquities, the Bembine Table of Isis has been the subject of much controversy. In a footnote, A. E. Waite–unable to differentiate between the true and the purported nature or origin of the Tablet–echoes the sentiments of J.G. Wilkinson, another eminent exotericus: “The original [Table] is exceedingly late and is roughly termed a forgery.” On the other hand, Eduard Winkelmann, a man of profound learning, defends the genuineness and antiquity of the Tablet. A sincere consideration of the Mensa Isiaca discloses one fact of paramount importance: that although whoever fashioned the Table was not necessarily an Egyptian, he was an initiate of the highest order, conversant with the most arcane tenets of Hermetic esotericism.

SYMBOLISM OF THE BEMBINE TABLE

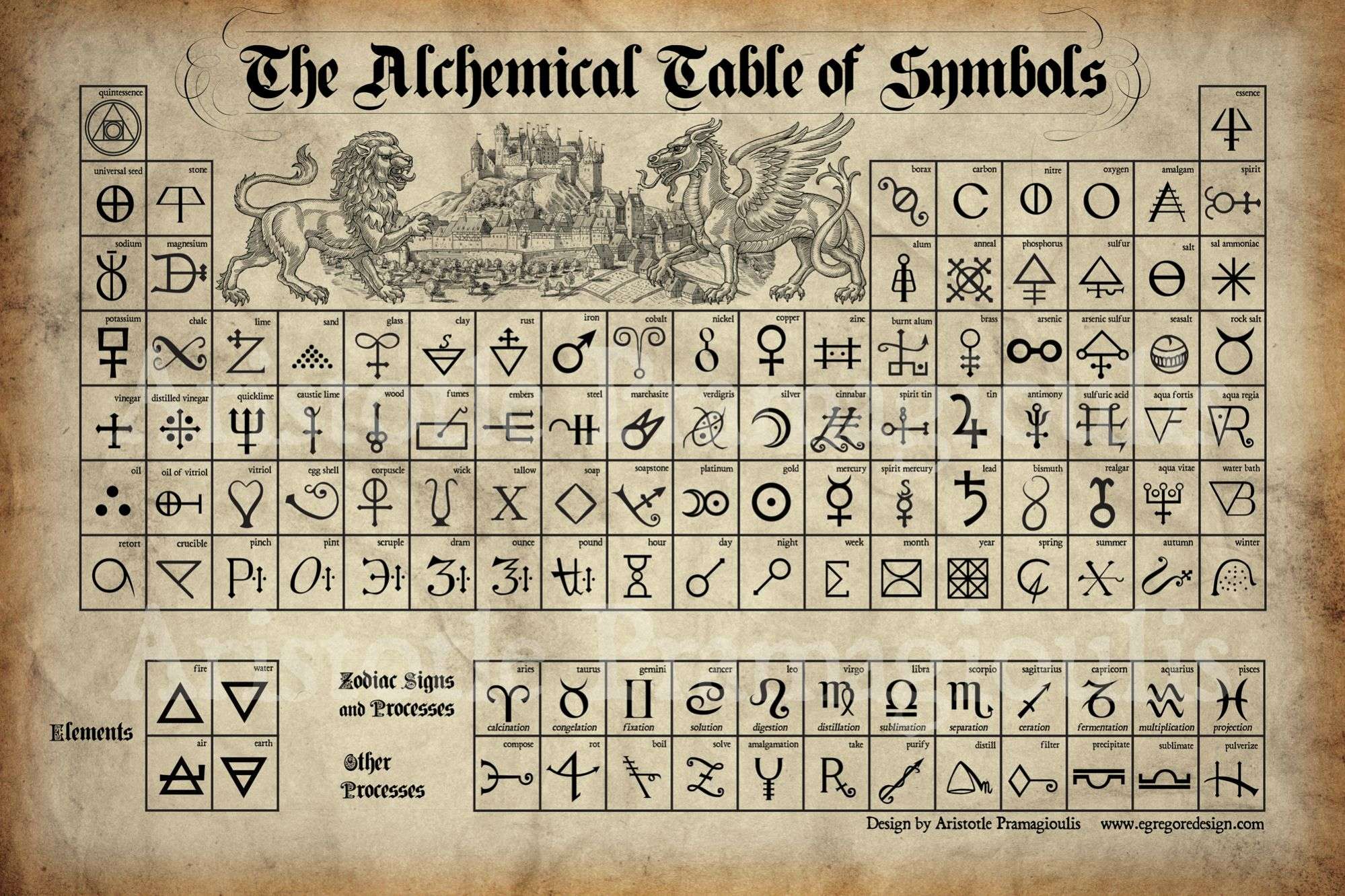

The following necessarily brief elucidation of the Bembine Table is based upon a digest of the writings of Kircher supplemented by other information gleaned by the present author from the mystical writings of the Chaldeans, Hebrews, Egyptians, and Greeks. The temples of the Egyptians were so designed that the arrangement of chambers, decorations, and utensils was all of symbolic significance, as shown by the hieroglyphics that covered them. Beside the altar, which usually was in the center of each room, was the cistern of Nile water which flowed in and out through unseen pipes. Here also were images of the gods in concatenated series, accompanied by magical inscriptions. In these temples, by use of symbols and hieroglyphics, neophytes were instructed in the secrets of the sacerdotal caste.

The Tablet of Isis was originally a table or altar, and its emblems were part of the mysteries explained by priests. Tables were dedicated to the various gods and goddesses; in this case Isis was so honored. The substances from which the tables were made differed according to the relative dignities of the deities. The tables consecrated to Jupiter and Apollo were of gold; those to Diana, Venus, and Juno were of silver; those to the other superior gods, of marble; those to the lesser divinities, of wood. Tables were also made of metals corresponding to the planets governed by the various celestials. As food for the body is spread on a banquet table, so on these sacred altars were spread the symbols which, when understood, feed the invisible nature of man.

In his introduction to the Table, Kircher summarizes its symbolism thus: “It teaches, in the first place, the whole constitution of the threefold world–archetypal, intellectual, and sensible. The Supreme Divinity is shown moving from the center to the circumference of a universe made up of both sensible and inanimate things, all of which are animated and agitated by the one supreme power which they call the Father Mind and represented by a threefold symbol. Here also are shown three triads from the Supreme One, each manifesting one attribute of the first Trimurti. These triads are called the Foundation, or the base of all things. In the Table is also set forth the arrangement and distribution of those divine creatures that aid the Father Mind in the control of the universe. Here [in the upper panel] are to be seen the Governors of the worlds, each with its fiery, ethereal, and material insignia. Here also [in the lower panel] are the Fathers of Fountains, whose duty it is to care for and preserve the principles of all things and sustain the inviolable laws of Nature. Here are the gods of the spheres and also those who wander from place to place, laboring with all substances and forms (Zonia and Azonia), grouped together as figures of both sexes, with their faces turned to their superior deity.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.