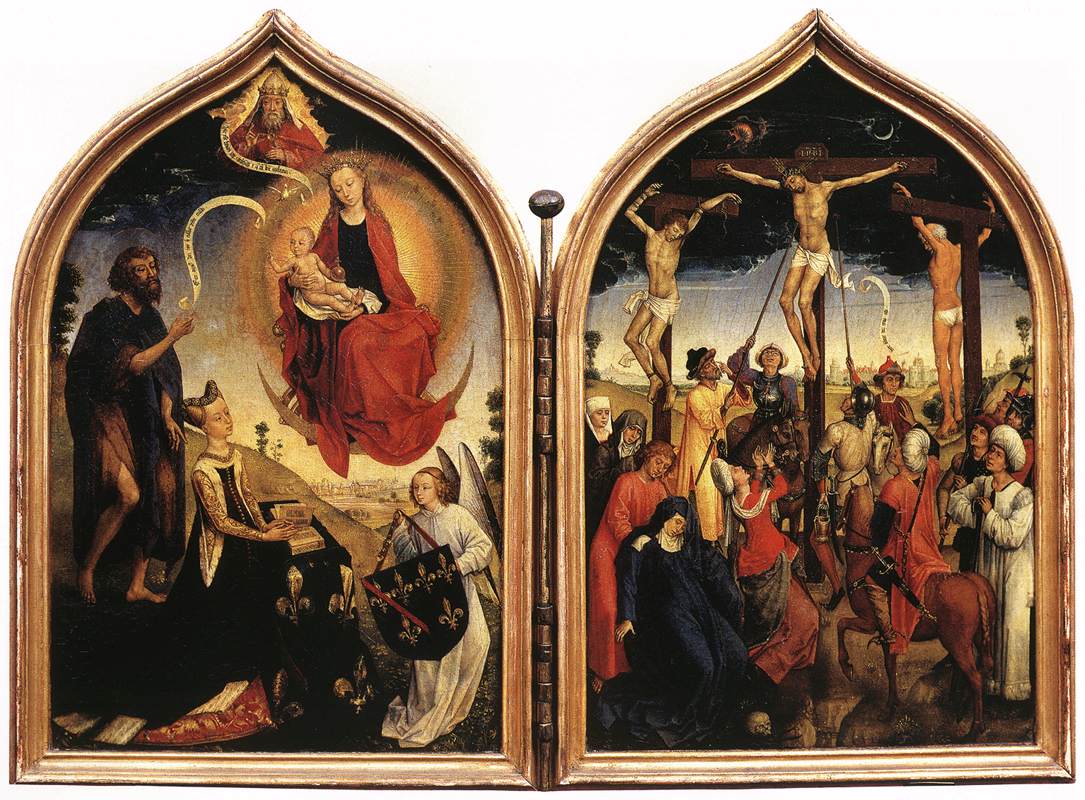

Concerning the crucifixion of the Persian Mithras, J. P. Lundy has written: “Dupuis tells us that Mithra was put to death by crucifixion, and rose again on the 25th of March. In the Persian Mysteries the body of a young man, apparently dead, was exhibited, which was feigned to be restored to life. By his sufferings he was believed to have worked their salvation, and on this account he was called their Savior. His priests watched his tomb to the midnight of the vigil of the 25th of March, with loud cries, and in darkness; when all at once the light burst forth from all parts, the priest cried, Rejoice, O sacred initiated, your God is risen. His death, his pains, and sufferings, have worked your salvation.” (See Monumental Christianity.)

In some cases, as in that of the Buddha, the crucifixion mythos must be taken in an allegorical rather than a literal sense, for the manner of his death has been recorded by his own disciples in the Book of the Great Decease. However, the mere fact that the symbolic reference to death upon a tree has been associated with these heroes is sufficient to prove the universality of the crucifixion story.

The East Indian equivalent of Christ is the immortal Christna, who, sitting in the forest playing his flute, charmed the birds and beasts by his music. It is supposed that this divinely inspired Savior of humanity was crucified upon a tree by his enemies, but great care has been taken to destroy any evidence pointing in that direction. Louis Jacolliot, in his book The Bible in India, thus describes the death of Christna: “Christna understood that the hour had come for him to quit the earth, and return to the bosom of him who had sent him. Forbidding his disciples to follow him, he went, one day, to make his ablutions on the banks of the Ganges * * *. Arriving at the sacred river, he plunged himself three times therein, then, kneeling, and looking to heaven, he prayed, expecting death. In this position he was pierced with arrows by one of those whose crimes he had unveiled, and who, hearing of his journey to the Ganges, had, with generation. a strong troop, followed with the design of assassinating him * * *. The body of the God-man was suspended to the branches of a tree by his murderer, that it might become the prey of vultures. News of the death having spread, the people came in a crowd conducted by Ardjouna, the dearest of the disciples of Christna, to recover his sacred remains. But the mortal frame of the redeemer had disappeared–no doubt it had regained the celestial abodes * * * and the tree to which it had been attached had become suddenly covered with great red flowers and diffused around it the sweetest perfume.” Other accounts of the death of Christna declare that he was tied to a cross-shaped tree before the arrows were aimed at him.

The existence in Moor’s The Hindu Pantheon of a plate of Christna with nail wounds in his hands and feet, and a plate in Inman’s Ancient Faiths showing an Oriental deity with what might well be a nail hole in one of his feet, should be sufficient motive for further investigation of this subject by those of unbiased minds. Concerning the startling discoveries which can be made along these lines, J. P. Lundy in his Monumental Christianity presents the following information: “Where did the Persians get their notion of this prophecy as thus interpreted respecting Christ, and His saving mercy and love displayed on the cross? Both by symbol and actual crucifix we see it on all their monuments. If it came from India, how did it get there, except from the one common and original centre of all primitive and pure religion? There is a most extraordinary plate, illustrative of the whole subject, which representation I believe to be anterior to Christianity. It is copied from Moor’s Hindu Pantheon, not as a curiosity, but as a most singular monument of the crucifixion. I do not venture to give it a name, other than that of a crucifixion in space. * * * Can it be the Victim-Man, or the Priest and Victim both in one, of the Hindu mythology, who offered himself a sacrifice before the worlds were? Can it be Plato’s second God who impressed himself on the universe in the form of the cross? Or is it his divine man who would be scourged, tormented, fettered, have his eyes burnt out; and lastly, having suffered all manner of evils, would be crucified? Plato learned his theology in Egypt and the East, and must have known of the crucifixion of Krishna, Buddha, Mithra [et al]. At any rate, the religion of India had its mythical crucified victim long anterior to Christianity,

THE TAU CROSS. The TAU Cross was the sign which the Lord told the people of Jerusalem to mark on their foreheads, as related by the Prophet Ezekiel. It was also placed as a symbol of liberation upon those charged with crimes but acquitted.

THE CRUX ANSATA. Both the cross and the circle were phallic symbols, for the ancient world venerated the generative powers of Nature as being expressive of the creative attributes of the Deity. The Crux Ansata, by combining the masculine TAU with the feminine oval, exemplified the principles of generation.

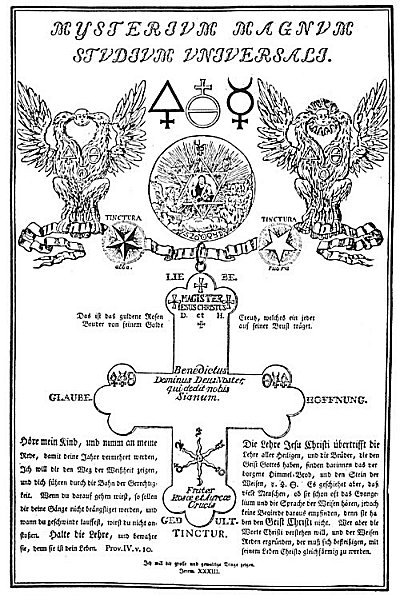

APOLLONIUS OF TYANA.

From Historia Deorum Fatidicorum. Concerning Apollonius and his remarkable Powers, Francis Barrett, in his Biographia Antiqua, after describing how Apollonius quelled a riot without speaking a word, continues: “He traveled much, professed himself a legislator; understood all languages, without having learned them; he had the surprising faculty of knowing what was transacted at an immense distance, and at the time the Emperor Domitian was stabbed, Apollonius being at a vast distance and standing in the market-place of the city, exclaimed, ‘Strike! strike!–’tis time, the tyrant is no more.’ He understood the language of birds; he condemned dancing and other diversions of that sort. he recommended charity and piety; he traveled over almost all the countries of the world; and he died at a very great age.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

![How, among innumerable other miracles of healing wrought by the wood of the cross, which King Oswald, being ready to engage against the barbarians, erected, a certain man had his injured arm healed [634 A.D.] | Book 3 | Chapter 2 How, among innumerable other miracles of healing wrought by the wood of the cross, which King Oswald, being ready to engage against the barbarians, erected, a certain man had his injured arm healed [634 A.D.] | Book 3 | Chapter 2](https://www.gnosticwarrior.com/wp-content/plugins/contextual-related-posts/default.png)