Between the Lamaico-Buddhistic and Roman Catholic articles of faith and ceremonies, there are fifty-one points presenting a perfect and striking similarity; and four diametrically antagonistic.

As it would be useless to enumerate the “similarities,” for the reader may find them carefully noted in Inman’s work on Ancient Faith and Modern, pp. 237-240, we will quote but the four dissimilarities, and leave every one to draw his own deductions therefrom:

[Column 1]

1. “The Buddhists hold that nothing which is contradicted by sound reason can be a true doctrine of Buddha.” [[Column continued on next page]]

[Column 2]

1. “The Christians will accept any non-sense, if promulgated by the Church as a matter of faith.” [[Column continued on next page]]

Page 541

[[Column 1 continued from previous page]]

2. “The Buddhists do not adore the mother of Sakya,” though they honor her as a holy and saint-like woman, chosen to be his mother through her great virtue.

3. “The Buddhists have no sacraments.”

4. The Buddhists do not believe in any pardon for their sins, except after an adequate punishment for each evil deed, and a proportionate compensation to the parties injured.

[[Column 2 from previous page]]

2. “The Romanists adore the mother of Jesus, and prayer is made to her for aid and intercession.” The worship of the Virgin has weakened that of Christ and thrown entirely into the shadow that of the Almighty.

3. “The papal followers have seven.”

4. The Christians are promised that if they only believe in the “precious blood of Christ,” this blood offered by Him for the expiation of the sins of the whole of mankind (read Christians) will atone for every mortal sin.

Which of these theologies most commends itself to the sincere inquirer, is a question that may safely be left to the sound judgment of the reader. One offers light, the other darkness.

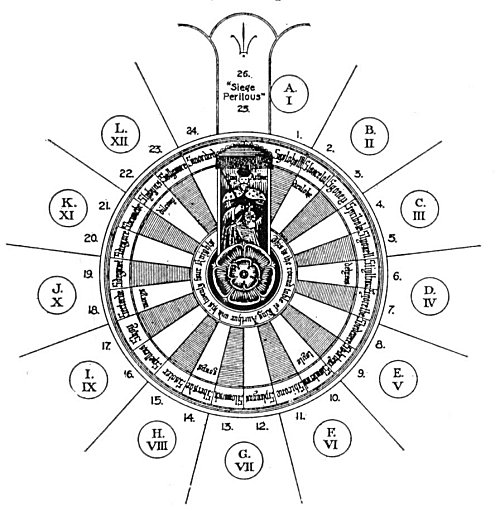

The Wheel of the Law has the following:

“Buddhists believe that every act, word, or thought has its consequence, which will appear sooner or later in the present or in the future state. Evil acts will produce evil consequences,good acts will produce good consequences: prosperity in this world, or birth in heaven . . . in some future state.”

This is strict and impartial justice. This is the idea of a Supreme Power which cannot fail, and therefore, can have neither wrath nor mercy, but leaves every cause, great or small, to work out its inevitable effects. “With what measure you mete, it shall be measured to you again” neither by expression nor implication points to any hope of future mercy or salvation by proxy. Cruelty and mercy are finite feelings. The Supreme Deity is infinite, hence it can only be JUST, and Justice must be blind. The ancient Pagans held on this question far more philosophical views than modern Christians, for they represented their Themis blindfold. And the Siamese author of the work under notice, has again a more reverent conception of the Deity than the Christians have, when he thus gives vent to his thought: “A Buddhist might believe in the existence of a God, sublime above all human qualities and attributes — a perfect God, above love, and hatred, and jealousy, calmly resting in a quiet happiness that nothing could disturb; and of such a God he would speak no disparagement, not from a desire to please Him, or fear to offend Him, but from natural veneration. But he cannot understand a God with the attributes and qualities of men, a God who loves and hates, and shows anger; a Deity, who, whether described to

Page 542

him by Christian missionaries, or by Mahometans, or Brahmans, or Jews, falls below his standard of even an ordinary good man.”

We have often wondered at the extraordinary ideas of God and His justice that seem to be honestly held by those Christians who blindly rely upon the clergy for their religion, and never upon their own reason. How strangely illogical is this doctrine of the Atonement. We propose to discuss it with the Christians from the Buddhistic stand-point, and show at once by what a series of sophistries, directed toward the one object of tightening the ecclesiastical yoke upon the popular neck, its acceptance as a divine command has been finally effected; also, that it has proved one of the most pernicious and demoralizing of doctrines.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.