For these Asiatic symbols of the contest of the Sun-God with the Dragon of darkness and Winter were imported not only into the Zodiac, but into the more homely circle of European legend; and both Thor and Odin fight with dragons, as Apollo did with Python, the great scaly snake, Achilles with the Scamander, and Bellerophon with the Chimæra. In the apocryphal book of Esther, dragons herald “a day of darkness and obscurity”; and St. George of England, a problematic Cappadocian Prince, was originally only a varying form of Mithras. Jehovah is said to have “cut Rahab and wounded the dragon.” The latter is not only the type of earthly desolation, the dragon of the deep waters, but also the leader of the banded conspirators of the sky, of the rebellious stars, which, according to Enoch, “came not at the right time”; and his tail drew a third part of the Host of Heaven, and cast them to the earth. Jehovah “divided the sea by his strength, and broke the heads of the Dragons in the waters.” And according to the Jewish and Persian belief, the Dragon would, in the latter days, the Winter of time, enjoy a short period of licensed impunity, which would be a season of the greatest suffering to the people of the earth; but he would finally be bound or destroyed in the great battle of Messiah; or, as it seems intimated by the Rabbinical figure of being eaten by the faithful, be, like Ahriman or Vasouki, ultimately absorbed by and united with the Principle of good.

Near the image of Rhea, in the Temple of Bel at Babylon, were two large serpents of silver, says Diodorus, each weighing thirty talents; and in the same temple was an image of Juno, holding in her right hand the head of a serpent. The Greeks called Bel

p. 500

[paragraph continues] Beliar; and Hesychius interprets that word to mean a dragon or great serpent. We learn from the book of Bel and the Dragon, that in Babylon was kept a great, live serpent, which the people worshipped.

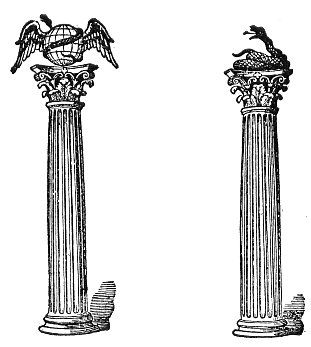

The Assyrians, the Emperors of Constantinople, the Parthians, Scythians, Saxons, Chinese, and Danes all bore the serpent as a standard, and among the spoils taken by Aurelian from Zenobia were such standards, Persici Dracones. The Persians represented Ormuzd and Ahriman by two serpents, contending for the mundane egg. Mithras is represented with a lion’s head and human body, encircled by a serpent. In the Sadder is this precept: “When you kill serpents, you will repeat the Zend-Avesta, and thence you will obtain great merit; for it is the same as if you had killed so many devils.”

Serpents encircling rings and globes, and issuing from globes, are common in the Persian, Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian monuments. Vishnu is represented reposing on a coiled serpent, whose folds form a canopy over him. Mahadeva is represented with a snake around his neck, one around his hair, and armlets of serpents on both arms. Bhairava sits on the coils of a serpent, whose head rises above his own. Parvati has snakes about her neck and waist. Vishnu is the Preserving Spirit, Mahadeva is Siva, the Evil Principle, Bhairava is his son, and Parvati his consort. The King of Evil Demons was called in Hindu_ Mythology, Naga, the King of Serpents, in which name we trace the Hebrew Nachash, serpent.

In Cashmere were seven hundred places where carved images of serpents were worshipped; and in Thibet the great Chinese Dragon ornamented the Temples of the Grand Lama. In China, the dragon was the stamp and symbol of royalty, sculptured in all the Temples, blazoned on the furniture of the houses, and interwoven with the vestments of the chief nobility. The Emperor bears it as his armorial device; it is engraved on his sceptre and diadem, and on all the vases of the imperial palace. The Chinese believe that there is a dragon of extraordinary strength and sovereign power, in Heaven, in the air, on the waters, and on the mountains. The God Fohi is said to have had the form of a man, terminating in the tail of a snake, a combination to be more fully explained to you in a subsequent Degree.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.