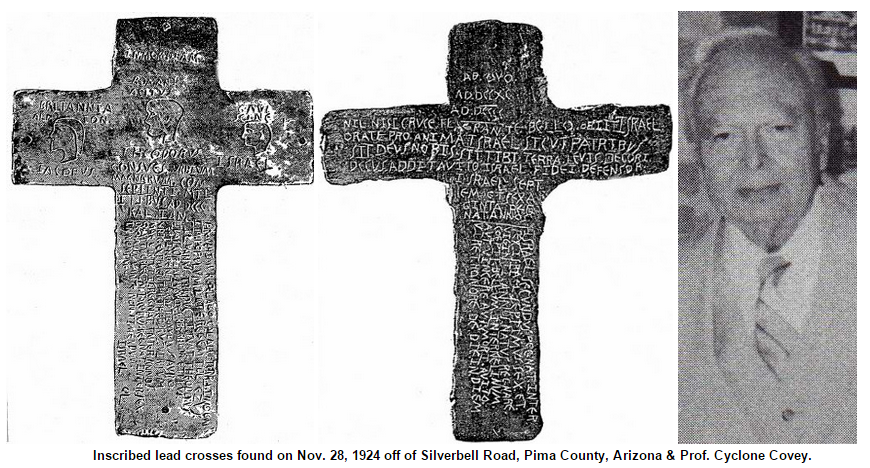

In 1924, a disabled veteran of World War I and history buff, Charles E. Manier took his family out for a Sunday drive along Silverbell Road in the Tuscon, Arizona area when he decided to stop in order to check out an old, abandoned lime kiln. That is when Manier saw something protruding from the enbankment. He then retrieved a shovel from his car, and proceeded to unearth an ancient sixty-two pound riveted lead cross that was actually two lead crosses riveted together.

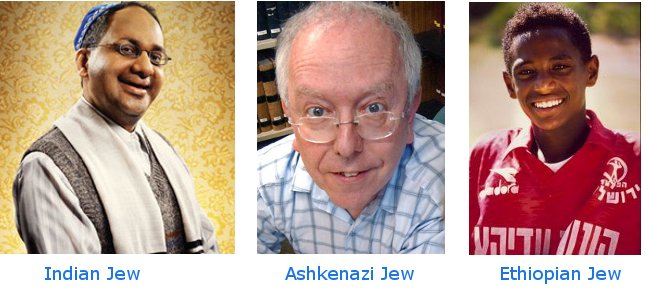

All together, Manier discovered from 31-32 lead objects between 1924 and 1930. The objects consisted of crosses, swords and ritual items, many of which were inscribed in both Latin and Hebrew. They are known as the Tucson artifacts, sometimes called the Tucson Lead Crosses, Tucson Crosses, Silverbell Road artifacts, or Silverbell artifacts.

After his find, Manier took the cross to Professor Frank H. Fowler, Head of the Department of Classical Languages at the University of Arizona, at Tucson, who determined the language on the artifacts was Latin. He also translated one line as reading, “Calalus, the unknown land”, from which the name of the supposed Latin colony was garnered.

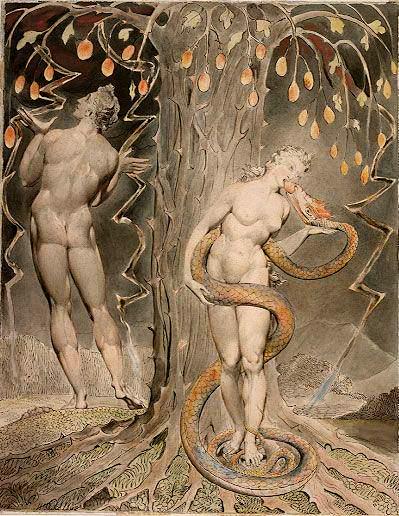

One of the crosses pictured below is an old Christian cross with a serpent wrapped around it much like the brass cross of Moses that bore the Latin inscription which translates: “We are borne on the sea from Rome to Calalus, an unknown land. They came in Anno Domini 775 and Theodore ruled the people.”

The cross and serpent was used up until approximately the 9th century before the time the Church had replaced the serpent with the figure of a man representing Jesus. The Father of English History, and Doctor of the Church, Saint Bede mentions this serpent on the cross changing into Jesus in the 8th and 9th centuries which would coincide with the dating of the Tuscon artifacts.

“And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in Him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” John 3:14, 15

There was also a Masonic square and compass symbol found at the site, but as Prof. Cyclone Covey (Wake Forest, emeritus Professor of History) had written in his 1975 book, Calalus: A Roman Jewish Colony in America from the Time of Charlemagne Through Alfred the Great that “most investigators were apparently too concerned with the fantastic tale as told on the various inscribed artifacts to pursue any possible masonic significance or origin.”

The tale, according to initial translations, involved Romans from early Medieval times sailing to North America. the controversy in his book titled Calalus: A Roman Jewish Colony in America from the Time of Charlemagne Through Alfred the Great. Covey was in direct contact with Thomas Bent by 1970, and planned to carry out excavations at the site in 1972, but was not allowed, due to legal complications preventing Wake Forest University from leading a dig at the site. Covey’s book proposes that the objects are from a Jewish settlement, founded by people who came from Rome and settled outside of present day Tucson around 800 AD.

Covey had written, “In the year 774, the six-four, flaxen-haired, long-nosed, to-high-voiced, miniskirted, 32-year-old Frank (Frenchman), Charlemagne, took a vacation from his siege of the Lombard king at Pavia, below Milan, to celebrate Easter at St. Peter’s in the shrunken city of Rome—to the dismay of Pope Hadrian 1, who made the best of the unannounced visit. The two concluded a pact, which may temporarily have deluded Hadrian into believing he still controlled Rome, let alone Ravenna.

But both he and the considerable faction of Jews under his jurisdiction must quickly have realized that the presence of the conformity-minded Frankish emperor augured coincidence if large numbers of Jews migrated the following year from Rome to the unknown land Calalus, as the Latin legend states on a snake-entwined ceremonial cross bearing also Hebrew words, found at a depth of six feet, about twenty feet west northwest of the Benjamin inscription cross. The sub rosa assistance of the pope in that interim before Charlemagne’s tentacles could tighten that far from Aachen, would go far to explain the ability of hundreds or even thousands of ghetto-dwellers to arrange shipping, supplies and a silent departure. This would also go far to explain a Jewish group’s continued honoring of Christian patriarchal symbols (talking about the crosses)—in this case symbolizing the approved civil sovereignty of the pope.” p. 33, 34

Sources:

Fell and Egyptian By Richard Flavin

Wikipedia

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.