very positive opinions. “The only case of spiritualism,” he writes, “I ever had the opportunity of examining into for myself, was as gross an imposture as ever came under my notice.”

What would this protoplasmic philosopher think of a spiritualist who, having had but one opportunity to look through a telescope, and upon that sole occasion had had some deception played upon him by a tricky assistant at the observatory, should forthwith denounce astronomy as a “degrading belief”? This fact shows that scientists, as a rule, are useful only as collectors of physical facts; their generalizations from them are often feebler and far more illogical than those of their lay critics. And this also is why they misrepresent ancient doctrines.

Professor Balfour Stewart pays a very high tribute to the philosophical intuition of Herakleitus, the Ephesian, who lived five centuries before our era; the “crying” philosopher who declared that “fire was the great cause, and that all things were in a perpetual flux.” “It seems clear,” says the professor, “that Herakleitus must have had a vivid conception of the innate restlessness and energy of the universe, a conception allied in character to, and only less precise than that of modern philosophers who regard matter as essentially dynamical.” He considers the expression fire as very vague; and quite naturally, for the evidence is wanting to show that either Prof. Balfour Stewart (who seems less in-

Page 423

clined to materialism than some of his colleagues) or any of his contemporaries understand in what sense the word fire was used.

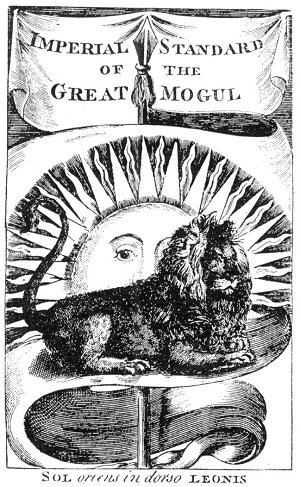

His opinions about the origin of things were the same as those of Hippocrates. Both entertained the same views of a supreme power, and, therefore, if their notions of primordial fire, regarded as a material force, in short, as one akin to Leibnitz’s dynamism, were “less precise” than those of modern philosophers, a question which remains to be settled yet, on the other hand their metaphysical views of it were far more philosophical and rational than the one-sided theories of our present-day scholars. Their ideas of fire were precisely those of the later “fire-philosophers,” the Rosicrucians, and the earlier Zoroastrians. They affirmed that the world was created of fire, the divine spirit of which was an omnipotent and omniscient GOD. Science has condescended to corroborate their claims as to the physical question.

Fire, in the ancient philosophy of all times and countries, including our own, has been regarded as a triple principle. As water comprises a visible fluid with invisible gases lurking within, and, behind all the spiritual principle of nature, which gives them their dynamic energy, so, in fire, they recognized: 1st. Visible flame; 2d. Invisible, or astral fire — invisible when inert, but when active producing heat, light, chemical force, and electricity, the molecular powers; 3d. Spirit. They applied the same rule to each of the elements; and everything evolved from their combinations and correlations, man included, was held by them to be triune. Fire, in the opinion of the Rosicrucians, who were but the successors of the theurgists, was the source, not only of the material atoms, but also of the forces which energize them. When a visible flame is extinguished it has disappeared, not only from the sight but also from the conception of the materialist, forever. But the Hermetic philosopher follows it through the “partition-world of the knowable, across and out on the other side into the unknowable,” as he traces the disembodied human spirit, “vital spark of heavenly flame,” into the AEthereum, beyond the grave.

This point is too important to be passed by without a few words of comment. The attitude of physical science toward the spiritual half of the cosmos is perfectly exemplified in her gross conception of fire. In this, as in every other branch of science, their philosophy does not contain one sound plank: every one is honeycombed and weak. The works of their own authorities teeming with humiliating confessions, give us the

Page 424

right to say that the floor upon which they stand is so unstable, that at any moment some new discovery, by one of their own number, may knock away the props and let them all fall in a heap together. They are so anxious to drive spirit out of their conceptions that, as Balfour Stewart says: “There is a tendency to rush into the opposite extreme, and to work physical conceptions to an excess.” He utters a timely warning in adding: “Let us be cautious that, in avoiding Scylla, we do not rush into Charybdis. For the universe has more than one point of view, and there are possibly regions which will not yield their treasures to the most determined physicists, armed only with kilogrammes and meters and standard clocks.” In another place he confesses: “We know nothing, or next to nothing, of the ultimate structure and properties of matter, whether organic or inorganic.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.