“For a man to conquer himself is the first and noblest of all victories.” – Plato

The Ancient Greeks divided the soul of a person into three different parts – the mind (nous), the spirit (thumos), and needs or desires (epithumia).

Humans could be considered the charitor in the middle.

These parts would have different biological and mental operating functions that could either work with one another to help a person live a good and healthy life or they could work against each other to cause a person to have a bad and unhealthy life.

As if each part had a mind of its own.

In order to make rational and good decisions, each of the three parts must work with one another in a balanced manner.

In Plato’s Republic, speaking through Socrates, he divides the soul into three sections: the rational (nous), spirited (thumos), and desiring (epithumia or appetites).

Plato further elaborates on his own tripartite theory of the soul as the following:

Nous – is related to the “mind or intellect and “reason”, which involves thoughts, reflections, and questioning and should be the controlling part of the soul that subjugates the appetites with the help of our thumos.

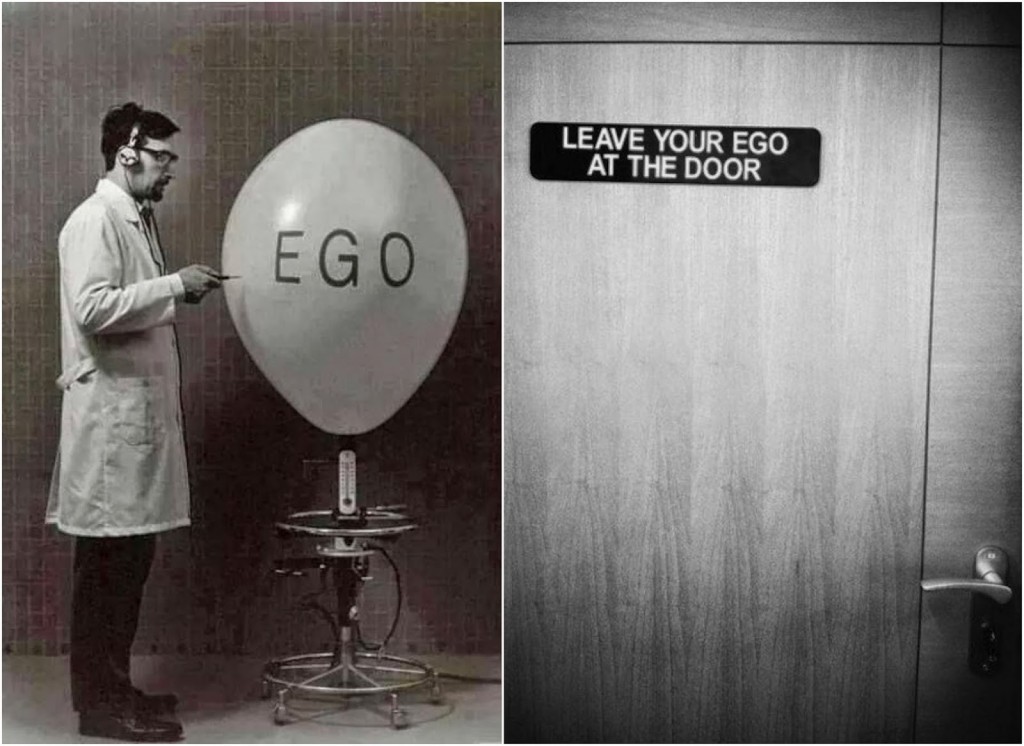

Thumos (Thymos) – is related to our spirit and the modern concept of the ego, emotions, and passions of which we feel sadness, anger, fear, courage, glory, love, etc. (the Republic IV, 439e);

Epithumia – is our desires or appetites, which is normally ascribed to our lower natures or bodily desires such as food, drink, sex, money, power, etc.

For Plato, when these three parts of the soul are balanced and work in combination with one another, this makes us better suited in our destined vocation, and is also the secret process for developing our innate ideas.

It is interesting how Plato’s description of the so-called “spirited element” ( to thumoeides or thumos) helps or works against the intellect (nous), but also in either subjugating or being subject to our appetites.

This is why Plato once said, “For a man to conquer himself is the first and noblest of all victories.”

And his student Aristotle followed with, “What lies in our power to do, lies in our power not to do.”

Plato believed that the thumos (spirit) was the source for desires, emotions, and sensitivities. And also various attributes such as bravery, determination, and nobility that also needed to be tempered by a need for civility, order, and justice.

Within the ideal city state, every citizen would possess a healthy thumos (spirit) within their souls.

This thumos (spirit) would allow citizens to uphold their honor and courageously assert their opinion within civic life. A citizen also knows how to maintain composure or restrict the thumos (spirit) if it were to passionate, violent or when it were misdirected.

When discussing his ideal state within the pages of The Republic, Plato, through the voice of Socrates, explains that the ideal guard or soldier would be possessed with a spirited sense of thumos and a desire to combat injustice.

Plato mentions thumos when commenting on a dog that is both loyal to his master, and dangerous to any evil-doer he may encounter.

“And is he likely to be brave who has no spirit, whether horse or dog or any other animal? Have you never observed how invincible and unconquerable is a spirit and how the presence of it makes the soul of any creature to be absolutely fearless and indomitable?”- Plato (Republic Book II)

In the dialog Phaedrus, Plato compares the human soul to a chariot that is being pulled by one white horse and one black horse, with a skilled charioteer at the reigns.

“First the charioteer of the human soul drives a pair, and secondly one of the horses is noble and of noble breed, but the other quite the opposite in breed and character. Therefore in our case the driving is necessarily difficult and troublesome.”-Plato (Phaedrus)

The black horse is said to represent men’s passions and appetites (epithumia).

The white horse is said to represent what in Greek is called thumos, which again, means the spirit or ego. And the charioteer is what Plato calls the noble breed or soul using the power of reason, which holds the reigns of both horses steadily through reason, while not allowing either to run wild.

This is a powerful image by Plato to describe how to balance these different parts (minds) of the soul in order to lead a balanced and healthy life.

One horse represents our day to day needs and desires or what could be called our animal instincts, and the other represents our divine instinct to pursue social pride or what we call nobility.

In Homer’s works, thumos is used to describe the internal psychological process of thought, emotion, volition, and motivation. It was the emotional state of man, to which his thinking and feeling belonged.

It is what motivates us to accomplish or will or what can be called our God given destinies.

When a Homer writes about a hero who is under duress, he will project his thumos to converse with or get angry with it as if he has two minds or personalities to contend with within himself.

Homer uses thumos to describe the way in which a hero thinks and what drives his passions and motivations.

A “thomeward” man has an inner strength that may be called upon when faced with certain death, but it also remains separate from him and drives its own course regardless of what may be going on externally to the person.

Therefore, we can say that the thumos is the most crucial component for any hero or nobility.

Homer represents Achilles as the only hero who speaks and questions his soul as “his great-hearted spirit” when he is unsure of how to proceed in battle. He uses thumos to show how Achilles is able to use logic and reason as he thinks out loud to himself, and arrives at important decisions.

The power or energy of the thumos could help a hero control his body and also be brave because it was a power or energy that was bigger than himself. It was something the hero initiated and tapped into, but it was also an agency that was separate from him.

The thumos not only can help a hero to be brave and stand their ground, but also acts as a metaphysical bond that ties him together with other heroes i.e., nobility who have similar thumos or spirits.

Thus creating invisible chains (Noosphere) that connect people to one another to assist not only in combat, but also in helping protect all that is good in society.

Cowards or weak people who do not have a strong thumos do not have the ability or God given right to tap into this energy or power.

As if by default, they are cut off from the source or God.

The Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher, Democritus used “euthymia” (i.e. “good thumos”) to refer to when our soul is calm and steadfast. Not being disturbed by fear, superstition, or passions.

Meaning that a person can have a bad thumos or a good one.

For Democritus, having euthymia was one of the main goals of human life.

Diogenes Laërtius had wrote about Democritus’ view as follows:

“The chief good he asserts to be cheerfulness (euthymia); which, however, he does not consider the same as pleasure; as some people, who have misunderstood him, have fancied that he meant; but he understands by cheerfulness, a condition according to which the soul lives calmly and steadily, being disturbed by no fear, or superstition, or other passion.”

In Seneca’s essay on tranquility, he defines euthymia as “believing in yourself and trusting that you are on the right path, and not being in doubt by following the myriad footpaths of those wandering in every direction.”

SOURCES:

Psychological Ideas in Antiquity. In: Dictionary of the History of Ideas. 1973-74 Long, A. A.

The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Douglass Cairns)

Homer (2003). The Iliad (Wordsworth Classics) (New ed.)

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.