Epimenides of Knossos: The Origins of Western Esotericism

For hundreds of years, Epimenides was one of the most famous ancient philosophers predating the great giants of Western philosophy such as Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, all of whom drew inspiration from his writings. (1) Throughout history, his stories and teachings have been passed down to us by some of the greatest philosophers who have ever lived, leaving an indelible mark on the culture and philosophy of ancient Greece and the whole Western world.

Over the course of many generations, Epimenides was immortalized within Greek history with his extraordinary intellectual and mythical god-like status, thereby elevating him to a divine-like status. As a result, his life and works have captivated the imagination of scholars and storytellers for thousands of years.

In this essay, I aim to shed light on the origins of our Western esoteric traditions, drawing from the perspectives of ancient philosophers and historians. According to some of these most esteemed thinkers, the roots of this tradition can be traced back to Epimenides and the enigmatic Orphic mysteries, originating in the land of Crete and Greece.

Both the Orphic and teachings of Epimenides can be found in the philosophies of some of the world’s greatest philosophers such as Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle and their intellectual successors such as the Pythagoreans and Neoplatonists who followed this tradition forming a direct lineage from Orpheus. (2) In examining their own sources for their philosophies, they all claim that both Orpheus and Epemenides had equally influenced their own ideas.

According to these accounts, both Orpheus and Epemenides lived at approximately the same time and in the same places with very similar accomplishments. For example, as Orpheus and Epemenides had accomplished, we find that they are similarly immortalized in myth and history for their efforts to revolutionize the secret mysteries in order to create a new state religion and also cleanse the land from a devastating plague.

According to Plato, Epimenides undertook the work assigned to him by the Delphic Oracle, which held a significant influence on the advancement of Hellenic society. (3) Aristotle said that he gave his oracles not about the future, but about things in the past that were obscure.

In myth and history, their influence on both ancient political and religious doctrines has served as the very foundation for shaping the course of Western philosophy and esotericism. Initial concepts that we find deeply intertwined within the philosophical and religious ideas of the collective imagination of many of the early Cretan and Greek philosophers, which became the very cornerstone of Western Esotericism, Philosophy, Gnosticism, and the later Abrahamic religions.

At the center of these ideas was the home of Epimenides and his ancestors, the island of Crete.

Two books Epimenides was said to have written that were mentioned by several eminent ancient authors were The History of Crete and Kretika or Cretika. The “History of Crete” is a comprehensive account of the origins, development, and notable events of the island of Crete.

Epimenides traces the history of the island from its mythical beginnings to the time of his own writing. The work is said to provide valuable insights into Cretan civilization, its social structures, religious practices, and the interplay of various cultural influences. Although the original text of the “History of Crete” has been lost, and our knowledge of its contents comes primarily from references and quotations found in later works by other authors.

“Kretika or Cretika,” on the other hand, is a collection of religious and moral teaching in the form of poems and hymns celebrating the glory and virtues of Crete. These poems praised the island’s natural beauty, its people’s achievements, and the valor of Cretan warriors.

Epimenides wrote;

“There is a land called Crete in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair land and a rich, begirt with water, and therein are many men innumerable, and ninety cities. And all have not the same speech, but there is confusion of tongues; there dwell Achaeans and there too Cretans of Crete, high of heart, and Cydonians there and Dorians of waving plumes and goodly Pelasgians.”

The “Kretika” served as a means to promote a deep understanding of religious beliefs and practices prevalent in ancient Crete. However, like the “History of Crete,” the original text of “Kretika” has not survived, and our knowledge of its contents is based on fragments and references in other ancient texts.

Diodorus Siculus, the first-century-BC historian of ancient Greece said that he relied upon Epimenides’ work for his Bibliotheca historica claiming that, “I have followed the most trustworthy authorities on Cretan affairs, Epimenides the Theologian, Dosiades, Sosicrates and Laosthenes.” (4)

Both Aristotle and Plutarch included Epimenides in the esteemed group known as the Seven Wise Men according to ancient tradition. The Seven Wise Men hold a significant position in the early stages of Hellenic history, as they played a pivotal role in shaping and consolidating Hellenism.

Plutarch wrote;

“Under these circumstances, they summoned to their aid from Crete Epimenides of Phaestus, who is reckoned as the seventh Wise Man by some of those who refuse Periander a place in the list. He was reputed to be a man beloved of the gods, and endowed with a mystical and heaven-sent wisdom in religious matters.

Therefore the men of his time said that he was the son of a nymph named Balte, and called him a new Cures. On coming to Athens he made Solon his friend, assisted him in many ways, and paved the way for his legislation.”(5)

What is certain, is that many esteemed authorities, from Plato and Aristotle onward, emphasized the religious, political, and social ramifications resulting from the life and work of Epimenides. Other philosophers, such as Parmenides and Heraclitus, drew upon his ideas to shape their own philosophies.

Parmenides, as discussed in “Metaphysics and Ethics in Epimenides’ Teachings” by A. Turner, adopted Epimenides’ emphasis on the existence of a singular reality, in his case, the concept of Being. Heraclitus, known for his philosophy of change and flux, incorporated Epimenides’ insights into the nature of reality and the paradoxes of existence. (6)

Being counted as a main authority for Siculus and among the Seven Wise Men in the early tradition not only attests to Epimenides’ authority among ancient philosophers of Greece, but also signifies his contribution to the fame and collective memory of the Phoenician and Hellenic people.

Now, let us examine these esoteric connections.

EPIMENIDES, PLATO, SAINT PAUL, AND CRETAN LIARS

Perhaps Epimenides is most often remembered for his famous quote known as the “Liar Paradox,” which challenges the very foundations of truth and logic. The quote is from his book called Cretica (Κρητικά) when Minos addresses the god, Zeus.

We find this verse initially appearing in Callimachus'(270 B.C.) Hymn to Jupiter/Zeus (verses 8-11):

“They say that thou, O Zeus, wast born in [Cretan] Ida’s mountains, and that thou wast born in Arcadia. Which, O Father, spoke falsely? The Cretans are always liars: and this we know, for thy tomb, O King, the Cretans fashioned; but thou didst not die, for thou existest always.”

Epimenides’ paradox is mentioned by Epimenides himself, as recorded by Diogenes Laertius in “Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers” (3rd century CE). However, it is important to note that the attribution of the paradox to Epimenides is not certain, and it could have been later attributed to him. (7)

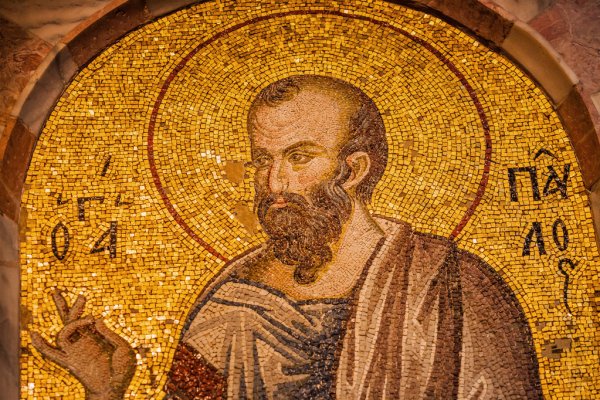

And later, during the Christian era, the apostle Paul references Epimenides’ paradox in the New Testament, specifically in the “Epistle to Titus” (Titus 1:12). Paul says about the Cretans’ reputation;

“One of themselves, a prophet of their own, said, The Cretans are always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies” (kata thêria, gasteres argai),” which is an allusion to the paradox.

This connection to Paul, Crete, and the Bible shows Epimenides actively influenced and possibly participated in these Gnostic movements. As I explained, he also influenced many of the early Greek philosophers and historians such as Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, and Diodorus Siclus, to name a few.

We also find the Epimenides’ Paradox in a discussion on liars in “Sophist” by Plato (4th century BCE). In Section 231, Plato mentions Epimenides as an example of a liar who paradoxically claims that all Cretans are liars. Although this particular quote doesn’t directly reference Epimenides’ statement, it engages with the idea of the paradox.

Plato wrote; “The Cretans, according to our account, have not only invented the story of the birth of Zeus, but they have also, as Epimenides says, declared all men to be liars.” (8)

Plato’s student and predecessor, Aristotle also mentions the same quote in his “Metaphysics;”

“But a man may ask whether what is said should be regarded as universally false or only as not universally true; for if what Epimenides says is true, it is false, and if false, it is true.” (9)

Moreover, the island of Crete held a significant place in the hearts of Cretans and Greeks alike, for it was venerated as the very cradle of Greek myths and religion. In particular, it was considered the sacred birthplace of Zeus, the revered father of gods and men.

PYTHAGORAS AND EPIMENIDES:

Pythagoras, the renowned mathematician and philosopher, is said to have encountered Epimenides during his travels to Crete. We are told that he was a student of Epimmenides. It is also well known that Pythagoras has played a pivotal role in the history of Western esotericism expanding upon the philosophical and mathematical doctrine with his followers, the Pythagoreans.

Pythagoras was spoken of and written about much more often. His great fame had the twin effects of making his name the focus of legends, which multiplied over the centuries, and of preserving the memory of the historical events of his time.

Although Epimenides was not directly associated with the Pythagorean school, several Pythagorean fragments and testimonies mention a connection between Pythagoras and Epimenides. These fragments, collected by various ancient authors, provide indirect evidence of Epimenides’ influence on Pythagoras and his followers.

The primary sources on Pythagoras, such as the works of Diogenes Laërtius, Iamblichus, and Porphyry, mention Pythagoras’ journey to Crete. Additionally, Plato’s dialogue “Phaedrus” depicts Socrates discussing the potential influence of Pythagorean thought, suggesting a connection between Pythagoras and Cretan philosophy. (10)

It is important to note that the primary source for this account is Diogenes Laertius’ book on Pythagoras. Laërtius, a doxographer who lived around 200 to 250 C.E., played a crucial role in preserving the biographies of ancient Greek philosophers through his notable work, Lives of Eminent Philosophers. The book consists of ten books that provide a wealth of information from the lives of nearly one hundred philosophers, including Pythagoras and 45 significant figures spanning from the seventh century C.C to the late second century C.E. (11)

A majority of Laërtius’ biographies name the teacher and student of each philosopher, and the people with whom they had personal encounters. To construct this comprehensive account, Laërtius drew information from numerous earlier works, many of which have been lost over time.

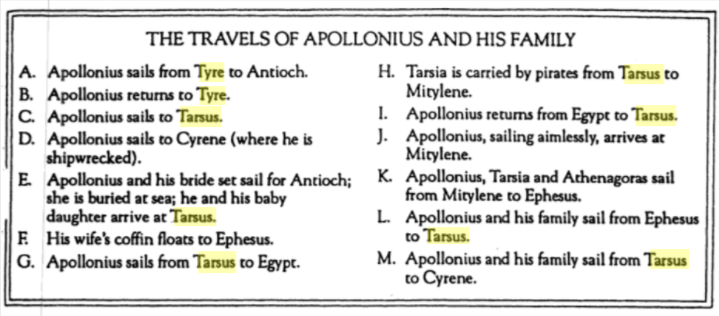

According to Laertius, Pythagoras embarked on extensive travels throughout the known world during his quest for knowledge with the intention of acquiring important initiations from various sources. As part of his journey, Pythagoras made a significant stop in Crete to meet Epimenides, a renowned figure of esoteric knowledge.

Epimenides possessed such valuable esoteric wisdom that Pythagoras himself sought initiation from him. Their meeting in Crete was a pivotal moment, as Pythagoras aspired to complete his initiation under Epimenides’ guidance. Together, they ventured into the renowned “Idaeon andron,” a cave of great significance. This cave was believed to be the birthplace of Zeus, the highest deity in Greek mythology.

Many biographical traditions recount Pythagoras’initiation into the mysteries in the Idean Cave on Mount Ida on Crete along with his journeys to culturally advanced eastern countries like Egypt and Babylon, as well as to Italy. This variation in narratives adds an intriguing layer to the understanding of Epimenides’ role and the sacred caves associated with Zeus.

Laertius wrote:

“When he was in Crete with Epimenides, he came down to Idaeon andron

Then (Pythagoras) visited Crete and descended to Idaion Andron accompanied by Epimenides, but also in Egypt to the depths;

but he also visited the shelters of the temples of Egypt. And learned about the gods in secret.”

Porphyry of Tyre , a Neoplatonic philosopher born in Tyre (Roman Phoenicia), mentioned the initiation of Pythagoras on the island of Crete at the cave located at Mount Ida, which was the original home to the Biblical Tribe of Judah (Idumeans, Judeans).

Porphyry wrote in the “Life of Pythagoras;”

“Going to Crete, Pythagoras besought initiation from the priests of Morgos, one of the Idaean Dactyli, by whom he was purified with the meteoritic thunder-stone. In the morning he lay stretched upon his face by the seaside; at night, he lay beside a river, crowned with a black lamb’s woolen wreath.

Descending into the Idaean cave, wrapped in black wool, he stayed there twenty-seven days, according to custom; he sacrificed to Zeus, and saw the throne which there is yearly made for him. On Zeus’s tomb, Pythagoras inscribed an epigram, “Pythagoras to Zeus,” which begins: “Zeus deceased here lies, whom men call Jove.” (11)

The name “Idaean Dactyli” is a reference to Mount Ida. Strabo, a Greek geographer and historian, provides geographical and historical information about Crete in his work “Geography.” Strabo had written, that the priests from Crete called the Curetes (Kuretes)

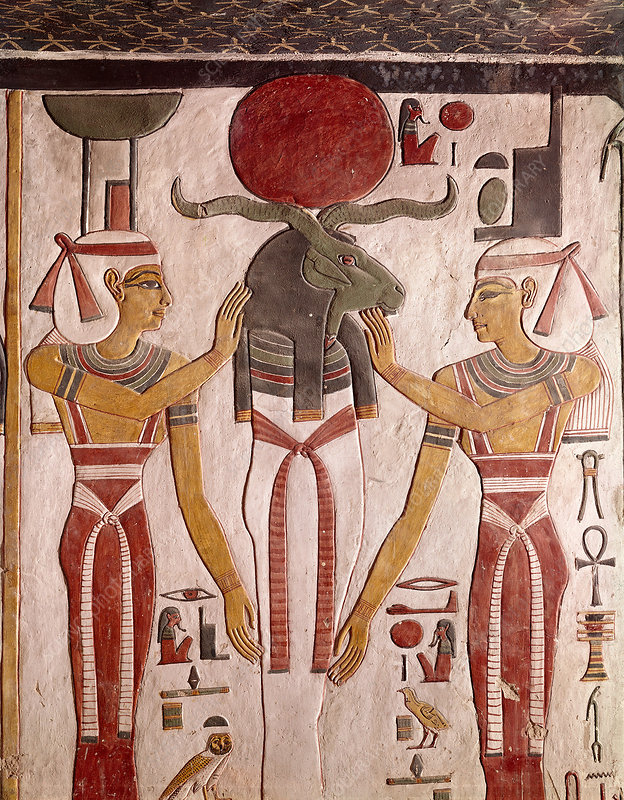

There are more mythological connections between Zeus, Mount Ida and the island of Crete. When the infant Zeus was born to his mother Rhea, his vengeful father Cronus had learned from Gaia and Uranus that his own son was destined to overcome him and become King. Rhea knowing what his father would do to him, had devised a plan to hide the real Zeus in a cave on Mount Ida in Crete, and in which she entrusted his care to the priesthood of the Curetes, who were also known as the “Ministers of Cybele.”

Although his writing does not explicitly discuss Epimenides’ influence on other philosophers, it offers contextual information about the time and place in which Epimenides and Pythagoras lived, helping to understand the cultural and intellectual milieu that facilitated philosophical exchanges.(12)

Epimenides’ ideas about paradoxes and the nature of truth deeply influenced Pythagoras’ philosophical pursuits. Pythagoras, known for his fascination with numbers and their mystical properties, was intrigued by Epimenides’ paradox and its implications for understanding the foundations of knowledge and logic.

According to “The Influence of Epimenides on Pythagorean Philosophy” by M. Williams, Pythagoras recognized the value of Epimenides’ teachings on religious devotion and the concept of the soul. Epimenides’ belief in the interconnection between the divine and mortal realms resonated deeply with Pythagoras’ own exploration of the harmony and order underlying the universe. (13)

The influence of Epimenides is especially evident in Pythagoras’ theory of the transmigration of souls, where he posited that the soul is immortal and can undergo successive reincarnations.

One notable concept that Pythagoras adopted from Epimenides was the notion of purification of the soul. Epimenides taught that the soul could be cleansed through spiritual practices and rituals, leading to a harmonious existence. Pythagoras embraced this idea, incorporating it into his theory of the transmigration of souls and the pursuit of moral and intellectual virtues leading to reason.

This concept can be found in the Abrahamic religions like in Christianity with saving your soul or being born again. Not everyone who emarks on the wrong path or lives ignorantly, immorally, and unethical is damned to a life of misery.

It is believed that Pythagoras incorporated elements of Epimenides’ paradoxes into his own teachings, which emphasized the pursuit of truth and the interconnectedness of all things. Pythagorean philosophy, with its emphasis on harmony, the eternal nature of the soul, and the mathematical underpinnings of the universe, owes a debt to Epimenides’ thought.

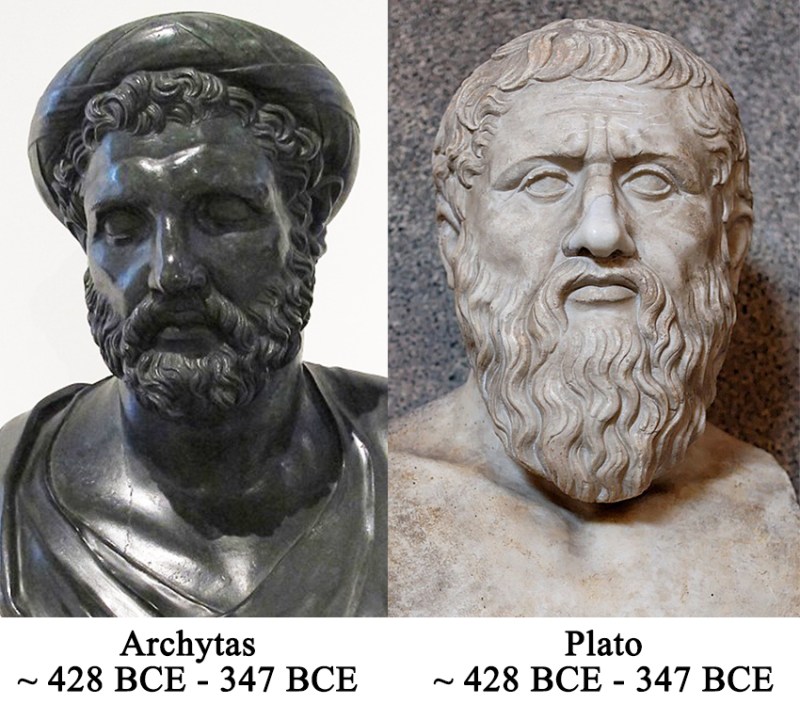

PLATO AND EPIMENIDES

Plato, the renowned philosopher and student of Socrates, was also influenced by Epimenides. Although there is limited direct evidence of their interaction, Plato’s works reflect Epimenides’ influence through shared philosophical themes and ideas. Epimenides’ belief in the existence of divine forces, the significance of myth and symbolism, and the pursuit of higher truths resonated strongly with Plato’s philosophical inquiries.

In Book 10 of “Laws, Plato’s portrayal of Epimenides in “Laws” draws heavily from the mythological traditions of ancient Greece to discuss the nature of divine law, prophecy, and the moral foundations of society. He presents Epimenides as a wise and virtuous individual who possesses an understanding of divine order and the significance of rituals and sacrifices. (14)

Plato describes Epimenides as a seer, someone who has a deep connection to the divine and the supernatural. Epimenides’ character serves as an authority on religious rituals and the interpretation of signs from the gods. He argues that these rituals are crucial for maintaining social cohesion and order.

One of Epimenides’ most famous contributions, the paradox of the “Cretan Liar,” had a lasting impact on Plato’s philosophical discourse. The paradox posed the question of whether a statement made by a Cretan asserting that all Cretans were liars could be true. This paradox challenged notions of truth, language, and self-reference, inspiring Plato’s exploration of these concepts in his dialogues.

Epimenides’ ideas on the existence of an ultimate reality beyond the sensory realm deeply influenced Plato’s theory of Forms or Ideas. Plato incorporated the notion of an eternal and unchanging realm of perfect forms, which closely aligned with Epimenides’ emphasis on the transcendental nature of truth. Additionally, Epimenides’ teachings on the significance of morality and the pursuit of virtue influenced Plato’s ethical philosophy, particularly his concept of the philosopher-king and the ideal city-state.

Plato mentions Epimenides in his Laws in the discussion between Megillus and Clinias in which Clinias claims a family connection to the Cretan prophet:

CLINIAS: My story, too, Stranger, when you hear it, will show you that you may boldly say all you wish. You have probably heard how that inspired man Epimenides, who was a family connection of ours, was born in Crete; and how ten years before the Persian War, in obedience to the oracle of the god, he went to Athens and offered certain sacrifices which the god had ordained; and how, moreover, when the Athenians were alarmed at the Persians’ expeditionary force, [642e] he made this prophecy —

“They will not come for ten years, and when they do come, they will return back again with all their hopes frustrated, and after suffering more woes than they inflict.” Then our forefathers became guest-friends of yours, and ever since both my fathers and I myself.

MYTHS AND LEGENDS

One notable aspect of Epimenides’ reputation among the Cretans was their belief in his divine origins. His mythical lineage can be traced back to the legendary King Minos, famous for his labyrinth and the Minotaur.

From a young age, he was said to have exhibited exceptional intelligence and exhibited a deep connection with nature, spending hours wandering the hills and caves surrounding his home. It was during one of these excursions that he encountered an enigmatic figure, a god-like presence who granted him an extraordinary gift.

Epimenides’ reputation as a sage grew exponentially when he ventured into the famed Labyrinth of Knossos, seeking answers to the mysteries of existence. Legend has it that he spent days wandering through its winding corridors, encountering mythical creatures and unraveling the secrets hidden within. Some accounts even suggest that he communed with the Minotaur, transforming it from a fearsome monster into a docile creature.

There is a famous legend surrounding the origination of the prophetic talents of Epimenides which the Greeks had usually embellished in mythology. The legend is, that while Epimenides was tending his father’s sheep, he is said to have fallen asleep for 40 or 57 years (on Mount Ida on the island of Crete) in a cave sacred to the King of Gods and Men, Zeus, and after which he reportedly awoke with the gift of prophecy.

The story appears to be an allegory, showing us that Epimenides was asleep “figuratively” until he reached his older years when he became enlightened.

At this moment, he finally awoke from his metaphorical slumber within the cave and attained inner enlightenment or Gnosis, becoming exceptionally wise in various disciplines and attaining a godlike status. This very cave gained worldwide renown as it appears to have served as an exclusive venue for initiation into the Orphic ceremonies and secret mysteries.

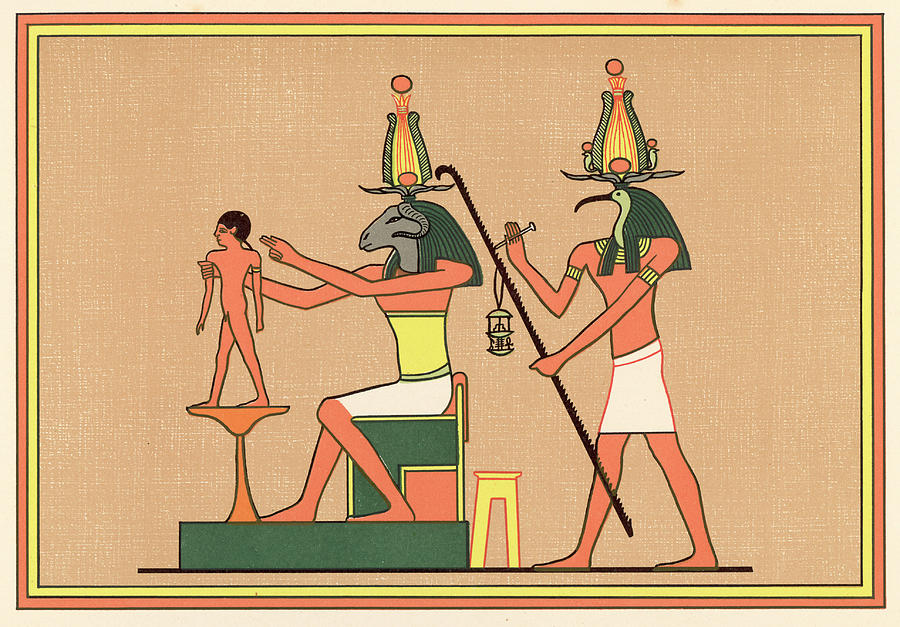

According to the accounts of the ancient historian, Theopompus, Epimeminides was said to have been divinely inspired to construct a sacred shrine dedicated to Zeus. He refers to the Creatn Prophets as the new Kouros or Koures, who had a significant connection to Zeus Cretagenes, possibly serving as his attendant or priest.

Though the precise nature of their association remains somewhat speculative, it is plausible that Epimenides served as an attendant or priest, carrying out sacred rites and rituals on behalf of the god. His actions and well-documented history exemplify his role as a defender and follower of Zeus, and also as one of the founders of the mystery schools, which left an immortal mark on the religious landscape of ancient Crete and the Ancient philosophers of Greece.

In Greek mythology, Jupiter was equated with Zeus, the king of the gods. The planet Jupiter has been associated with various names in different mythologies throughout history. The Romans also identified the planet with their supreme deity, giving him the same name. These associations can be traced back to the ancient Greeks and Romans who observed the planet and attributed its characteristics to their respective gods.

Plutarch refers to him as the “New Kouretes,” and the Cretans regarded his mother as the nymph Balte (Βάλτη) [2]. The divine connection attributed to Epimenides reflects the high regard in which he was held by his fellow Cretans.

Plutarch mentions both Epimenides and Solon were in Athens at the same time, and on friendly terms. The purification of Athens by Epimenides is generally assigned to B.c. 596 — 595, shortly before the archonship of Solon in 594. (15)

Epimenides assisted with the proper methods for the regulation of the Athenian Commonwealth to restore law and order. His expertise in sacrifices and the reform of funeral practices greatly assisted Solon in his efforts to reform the Athenian state.

Plutarch also said that Epimenides was almost like a messiah to the Greeks at the time because he had purified Athens and that the only reward he would accept was a branch of the sacred olive, and a promise of perpetual friendship between Athens and Knossos.

Plutarch wrote;

“Epimenides purified Athens after the pollution brought by the Alcmeonidae, and that the seer’s expertise in sacrifices and reform of funeral practices were of great help to Solon in his reform of the Athenian state. The only reward he would accept was a branch of the sacred olive, and a promise of perpetual friendship between Athens and Knossos.”

Maximus of Tyre confirms this event in the 2nd century CE;

“There came to Athens also another Cretan named Epimenides. He was marvelously skilled in the things of God, so that he saved the city of the Athenians when it was perishing through pestilence and sedition; and he was skillful in these matters, not because he had learned them, but, as he related, long sleep and a dream had been his inspiration … he had come into relations with the gods and the oracles of the gods and Truth and Justice.

For Solon had proclaimed at the time;

“In the day of vengeance, dark Earth, mightiest mother of the gods of Olympus, will be my surest witness of this, Solon’s account from whom I removed pillars planted in many places, and whom I freed from her bonds. Many citizens, who had been sold into slavery under the law or against it, I brought back to Athens their home; some of them spoke Attic no longer, their speech being changed in their many wanderings. Others who had learnt the habits of slaves at home, and trembled before a master, I made to be free men.

All this I accomplished by authority, uniting force with justice, and I fulfilled my promise.” (16)

Epimenides was said to have founded numerous religious organizations and installed statues of the gods throughout the streets of Athens. His intention was to instill in the minds of Athenians the constant presence of divine nature in various forms, where no indecency is allowed and everything must be regarded as sacred and untainted.

The ultimate goal and outcome were the thorough purification of the city and the establishment of virtuous guidelines for communal existence. It was imperative for the citizens to dwell in the ever-present aura of the divine.

Pausanias reports, that when Epimenides died, his skin was found to be covered with tattoo writing. Some modern scholars have seen this as evidence, that Epimenides was heir to the shamanic religions of Central Asia, because tattooing is often associated with shamanic initiation.”

He also places Epimenides at Knossos and claims he was killed and buried near the statue of Athena. Pausinias wrote:

“By the Canopy is a circular building [in Sparta], and in it images of Zeus and Aphrodite surnamed Olympioi. This, they say, was set up by Epimenides, but their account of him does not agree with that of the Argives, for the Lakedaimonians deny that they ever fought with the Knossians.”

[2.21.3] A sanctuary of Athena Trumpet they say was founded by Hegeleos. This Hegeleos, according to the story, was the son of Tyrsenus, and Tyrsenus was the son of Heracles and the Lydian woman; Tyrsenus invented the trumpet, and Hegeleos, the son of Tyrsenus, taught the Dorians with Temenus how to play the instrument, and for this reason gave Athena the surname Trumpet.

Before the temple of Athena is, they say, the grave of Epimenides. The Argive story is that the Lacedaemonians made war upon the Cnossians and took Epimenides alive; they then put him to death for not prophesying good luck to them, and the Argives taking his body buried it here.”

CONCLUSION:

Epimenides of Crete, with his paradoxes and philosophical ideas, left an enduring legacy on the development of Western philosophy. Through his influence on Socrates, Pythagoras, Plato, and other great philosophers, Epimenides’ exploration of truth, language, and metaphysics contributed to both the foundation and evolution of philosophical thought.

As an intermediary between the earthly and divine realms, Epimenides’ influence reached far beyond the confines of his immediate surroundings. His reputation as a philosopher, religious leader, and visionary extended throughout Greece and into Italy, capturing the attention and admiration of people from various parts of the world.

As we delve into the works of these philosophers and examine their ideas, we can trace the threads of Epimenides’ influence, highlighting the lasting impact of his contributions on philosophical discourse throughout the ages. Although direct references to Epimenides may be scarce, the parallels between their ideas, as found in primary sources such as Diogenes Laertius, Plato’s dialogues, and Aristotle’s works, suggest a deep and lasting influence.

Additionally, Pythagorean fragments, testimonies, and anecdotes collected by authors like Aelian offer indirect evidence of the connection between Epimenides and Pythagoras. While the exact extent of Epimenides’ influence may remain a matter of speculation, the interplay of their philosophical ideas demonstrates the rich and interconnected philosophical themes and concepts in their works highlighting the lasting influence on Western Esotericism.

Epimenides’ role in shaping the metaphysical and spiritual landscape of the time was widely acknowledged and respected. His presence and influence epitomized the deep connection between the mortal and divine realms, leaving an indelible mark on the religious consciousness of the ancient world that lasts until this very day.

I believe that the immortal story of Epimenides enshrined as the mythical Orpheus proves the origins of our Western religious and esoteric traditions. An ancient custom that is also connected to the sacred history of the island of Crete, solidifying its status as a spiritual epicenter for the various Gnostic and philosophical schools that came after throughout history.

SOURCES:

1. Guthrie, W.K.C. “A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans.” Cambridge University Press, 1962.

2. Forsyth, Neil. “Epimenides of Knossos.” In “The Oxford Classical Dictionary,” edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, 4th ed., 525-526. Oxford University Press, 2012

3. PLATO LAWS – § 642

4. Diodorus Siculus, “Library of History,” Book 5.77-78.

5. Plutarch, “Life of Solon,” in Plutarch’s Lives, trans. Bernadotte Perrin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914

6. Metaphysics and Ethics in Epimenides’ Teachings” by A. Turner

6. Guthrie, W. K. C. (1980). “A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans.

7. Laërtius, Diogenes. “Lives of Eminent Philosophers.” Translated by R. D. Hicks, Harvard University Press, 1925

8. Plato, “Phaedrus,” 260d

9. Aristotle, “Metaphysics,” Book 4, Part 7

10. Life of Pythagoras (1920). English translation

9. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924), 10.4.14

10. The Influence of Epimenides on Pythagorean Philosophy by M. Williams

11. Laërtius, Diogenes. “Lives of Eminent Philosophers.” Translated by R. D. Hicks, Harvard University Press, 1925

12. Strabo, “Geography,” in The Geography of Strabo, trans. Horace Leonard Jones

13. The Influence of Epimenides on Pythagorean Philosophy” by M. Williams

14. Plato. “Laws.” Translated by Trevor J. Saunders, Penguin Classics, 1970

15. Plutarch, Life of Solon, 12; Aristotle, Ath. Pol. 1

16. Asianic Elements in Greek Civilisation: The Gifford Lectures in the University of Edinburgh – Chapter 3 1915-16: Sir Ramsay

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.