The Orphic Mysteries: The Origins of Western Esotericism & Symbolic Freemasonry

The ancient Greek world was a rich tapestry of religious and philosophical ideas, with diverse cults and mystery traditions offering individuals different pathways to a deeper understanding of the divine and the self.

Among these, the Orphic Mysteries emerged in approximately the 6th Century BC as a prominent philosophical movement, characterized by its unique mythology, rituals, and esoteric teachings. (1)

Rooted in the mythological and ritualistic traditions of the Orphic movement, these mysteries offered a path to spiritual enlightenment and liberation. Numerous sources contribute to our understanding of Orpheus and his significance in Greek mythology.

Throughout history, numerous renowned philosophers and historians, spanning several centuries, have asserted that Orpheus existed as an actual human being, elevating him to a god-like status. His life story is recounted in various Greek myths, weaving together elements of music, heroism, and supernatural abilities.

According to these accounts, his accomplishments revolved around his efforts to revolutionize the state religion and cleanse the land from a devastating plague.

The Orphic teachings can be found in the philosophies of renowned thinkers such as Pythagóras, Socrates (Sôkrátîs), Plato (Plátôn), and their intellectual successors such as the Pythagoreans and Neoplatonists who followed in this tradition forming a direct lineage from Orpheus. (2) His political and religious doctrines served as the foundation for shaping the course of Western philosophy as a whole.

As the 19th century historian and expert Thomas Taylor wrote;

“For all the Grecian theology is the progeny of the mystic tradition of Orpheus; Pythagoras first of all learning from Aglaophemus the orgies of the Gods, but Plato in the second place receiving an all-perfect science of the divinities from the Pythagoric and Orphic writings.” (3)

The various cults surrounding the teachings of Orpheus are prominently featured in these ancient texts, solidifying his status as a significant figure in the mythological pantheon. He is credited as being the founder of the theology of the Greeks such as Eleusisian mysteries and the Mysteries of Dionysos.

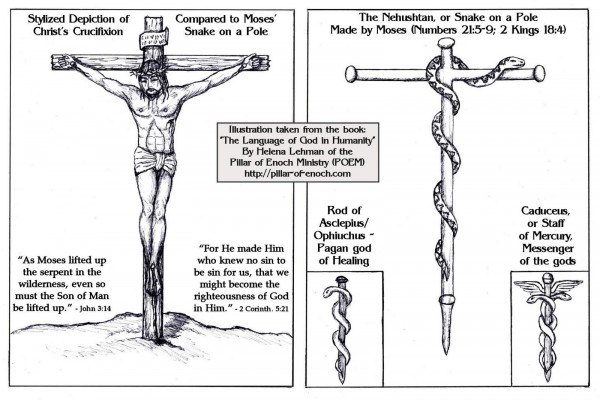

According to historical accounts, it is believed that the ancient Greek Mystery Cults established by Orpheus at Eleusis were heavily influenced by Egyptian traditions, which were transmitted through Ancient Phoenicia, the island of Crete, and Greece.

Diodorus Siculus, the 2nd century Greek historian, who is best known for his monumental work on universal history of the world, “Bibliotheca Historica” (Library of History), said that he relied on the work of Orpheus as one of his main sources.

Siculus claimed that he was held in such high esteem because he was the most knowledgeable man of the time who was honored by both the Greeks and the Egyptians. He also mentions that the rituals associated with Osiris, an Egyptian god, were remarkably similar to those of Dionysus, who was said to be a priest of Orpheus.

Siculus wrote:

“In After-times, Orpheus, by reason of his excellent Art and Skill in Musick, and his Knowledge in Theology, and Institution of Sacred Rites and Sacrifices to the Gods, was greatly esteemed among the Grecians, and especially was received and entertained by the Thebans, and by them highly honored above all others; who being excellently learned in the Egyptian Theology, brought down the Birth of the ancient Osiris, to a far later time and to gratify the Cadmeans or Thebans, instituted new Rites and Ceremonies, at which he ordered that it should be declared to all that were admitted to those Mysteries, that Dionysus or Osiris was begotten of Semele by Jupiter.

The People therefore partly through Ignorance, and partly by being deceived by the dazzling Luster of Orpheus his Reputation, and with their good Opinion of his Truth and Faithfulness in this matter (especially to have this God reputed a Grecian, being a thing that humored them) began to use these Rites, as is before declared. And with these Stories the Mythologists and Poets have filled all the Theaters, and now it’s generally received as a Truth, not in the least to be questioned.” (4)

The 20th-century historian and author, Otto Kern said in his Orphicorum Fragmenta that this testimony, from Diodorus of Sicily, says that Orpheus took his mystic rites from Egypt and that the Egyptian rite of Osiris is the same as that of Dionysus, the name alone being changed.

The parallels between the Egyptian and Greek mysteries extended beyond Dionysus and Osiris. Diodorus also noted that the Eleusinian mysteries shared similarities with the rites of Isis and Demeter.

“Orpheus, for instance, brought from Egypt most of his mystic ceremonies, the orgiastic rites that accompanied his wanderings, and his fabulous account of his experiences in Hades. For the rite of Osiris is the same as that of Dionysus, and that of Isis very similar to that of Demeter, the names alone having been interchanged; and the punishments in Hades of the unrighteous the Fields of the Righteous, and the fantastic conceptions, current among the many, which are figments of the imagination, all these were introduced by Orpheus in imitation of Egyptian funeral customs.” (5)

This further supports the notion that there was an intermingling of religious practices and beliefs between these ancient cultures of Greece and Egypt.

According to Pausanias, a Greek historian from the second century, individuals seeking knowledge (gnosis) and spiritual enlightenment would become initiates of the Mystery Schools established by Orpheus. These schools were dedicated to teaching ceremonial magic, unraveling the mysteries of the divine realms, and imparting the wisdom of herbal remedies for healing and warding off divine wrath.

Pausanias noted that both men and women flocked to these schools in great numbers, desiring purification and forgiveness for their unholy actions, so that they could lead virtuous lives that pleased the gods and gained their favor. (6)

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), one of the world’s most prominent Swiss psychiatrists and psychoanalysts, acknowledged the significance of Orphism on the world’s religions and cultures. Jung wrote that Ophism “inspired the religious ruminations and philosophic speculation of many centuries” and it offered “initiation into the secrets of the earth,” suggesting a deep connection with the mysteries of the natural world. (7)

For example, one of the central aspects of the Orpheus myth is his descent into the Underworld to retrieve his deceased wife, Eurydice. This journey is laden with symbolism and mirrors the hero’s journey archetype, which Jung believed was a recurring pattern in myths and religious tales worldwide.

Unlike the rites of Osiris and Isis, which primarily involved lamentations for the deaths of the deities associated with agriculture and vegetation, the Orphic Mysteries focused on the spiritual enlightenment of the initiate. (8)

Jung viewed Orphism as an attempt to reconcile the opposites within the individual psyche. He saw it as a profound expression of the human psyche’s desire for transcendence and spiritual liberation. He believed that Orphism represented a collective striving for connection with the divine, reflecting the innate human longing for a deeper understanding of the self and the cosmos.

In his book “Psychology and Alchemy,” he stated, “Orphism was a psychology of religion with a strong Gnostic coloring, representing the sum total of philosophical and religious endeavors to explain life as a meaningful whole.” Jung recognized the Orphic tradition as a quest for unity and wholeness, aiming to bridge the gap between conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche. (9)

In “The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious” (1934-1954), Jung discussed the hero’s journey as a transformative process of self-discovery, representing the individual’s confrontation with the unconscious and the integration of its contents. Orpheus’ descent into the Underworld signifies a quest for personal growth and spiritual development, echoing the individuation process in Jungian psychology. (10)

THE ORPHIC CONNECTION TO FREEMASONRY

This philosophical lineage and connection to the ancient mystery schools of Greece and Crete also continues on to today through the teachings of Gnosticism, religion, Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, and the Illuminati. Many of our most prominent scholars have acknowledged Orphic influences on our Western Esoteric mystery traditions.

One of the oldest connections is to Pythagoras, who lived in the 6th century BC. He was a Greek philosopher, mathematician and spiritual leader. He founded the philosophical and religious school of Pythagoreanism. Pythagoras’ teachings were also transmitted to the Western world through prominent medieval alchemists and subsequent practitioners of magic and secret societies, including the fraternities of Freemasonry and the Illuminati, in which Pythagoras played a central role.

This influence can be attributed to the origins of the Western mystery traditions along with their syncretic nature, where ideas, symbols, and religious customs have migrated from Egypt to Crete and Greece to the rest of the Western world, while sharing many of the same customs and rituals between different societies and cultures. These migrations of people which include language, history, religion, and Freemasonry can be traced throughout history to their true origins.

According to the Italian philosopher, scholar, and current Grand Master of the Academy of the Illuminati, Giuliano Di Bernardo;

“Orphism has had a considerable influence on the nascent philosophy not so much over the doctrine of reincarnation as for the dualistic conception of man. For the first time, man is understood as personifying two opposed principles: the immortal soul and the mortal body. This gives rise to a dualism that will cross the entire span of the history of philosophical thought up to our own days. Without Orphism, we would be unable to explain Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and all the philosophers who draw upon them.”

“As far as the initiatory foundation is concerned, between the Freemasonry and the Order of the Illuminati there are no differences: they are both heirs of the ancient Orphic and Pythagorean mysteries. The differences when compared to the present practices can pertain to the symbols, the rituals and the ceremonies.” (11)

Therefor, students of Western Esotericism and true symbolic Masonry should have a firm understanding of Orphic history. Famous Freemason and scholar Albert Pike, in his seminal work “Morals and Dogma,” suggests a Masonic connection to the Orphic Mysteries. Pike wrote;

“The distinction between the esoteric and exoteric doctrines (a distinction purely Masonic), was always and from the very earliest times preserved among the Greeks. It remounted to the fabulous times of Orpheus; and the mysteries of Theosophy were found in all their traditions and myths. And after the time of Alexander, they resorted for instruction, dogmas, and mysteries, to all the schools, to those of Egypt and Asia, as well as those of Ancient Thrace, Sicily, Etruria, and Attica.” (12)

The renown 20th century Masonic philosopher and historian, 33rd Degree Freemason, Many. P. Hall said:

“According to Iamblichus and Proclus, the Grecian theology was derived from the teachings of Orpheus. From Orpheus the doctrine descended to Pythagoras, and from Pythagoras to Plato. These three men together were the founders and disseminators of the Secret Doctrine which had been brought from Asia in the second millennium B. C.

In the words of Proclus, “What Orpheus delivered mystically through arcane narrations, this Pythagoras learned when he celebrated orgies in

the Thracian Libethra, being initiated by Aglaophemus in the mystic wisdom which Orpheus derived from his mother Calliope, in the mountain Pangaeus.” (13)

The influence of Orphic ideas within Freemasonry can be seen when examining Freemasonry from both a philosophical and symbolic perspective. One of the key aspects that highlights this symbolic connection between the Orphic Phanes, Plato’s Demiurgic Craftsman, and the Masonic Grand Architect of the Universe becomes readily apparent.

Both the Orphic mysteries and Freemasonry advocate for moral conduct, personal transformation, and the pursuit of divine knowledge. While the specific doctrines and practices may differ, the underlying principles of virtue, integrity, self-improvement, and enlightenment connect these traditions across time.

According to Dr. Nicolas Laos the Grand Master of the Autonomous Order of the Modern and Perfecting Rite of Symbolic Masonry (A∴O∴M∴P∴R∴S∴M∴), the beginning of Western esotericism, along with the Freemasons and the Illuminati originates with the ancient Orphic mysteries:

“Adam Weishaupt founded the Order of the Illuminati on 1 May 1776 in Bavaria.

Its declared purpose was to bring its members to the highest degree of morality and virtue, to free their minds from prejudice and superstition, and to reform the world by defeating the evils that afflict it.

As regards Freemasonry, Weishaupt maintained that his Order should remain distinct from it because the mysteries of Freemasonry were too puerile and too easily accessible to public opinion. The consequence was that the grades and rituals of the Illuminati were different from those of the Freemasons.

Moreover, the Order of the Illuminati, being a specific interpretation of the millenary esoteric tradition that starts with Orphism in the sixth century B.C.E., presents some common characteristics with other initiatory societies, such as the Rosicrucian Movement and Freemasonry.

According to many ancient Greek philosophers and mythologists, Orpheus founded the Orphic Mysteries, a system of mystical religious anthropology. The rites of those secret mysteries were based on the myth of Dionysus Zagreus, the son of Zeus and Persephone.

When Zeus proposed to make Zagreus the ruler of the universe, the Titans disagreed, and they dismembered the boy and devoured him. Athena saved Zagreus’s heart and gave it to Zeus, who swallowed the heart, from which was born the second Dionysus Zagreus.”

Nicolas Laos continues;

“Moreover, Zeus destroyed the Titans with lightning. From the ashes of the Titans sprang the human race, who were part divine (Dionysus) and part evil (Titan). This double aspect of human nature, the Dionysian and the Titanic, plays a key role in Orphism.

The Orphics affirmed the divine origin of the soul, but they believed that the soul could be liberated from its Titanic inheritance and could achieve eternal bliss through initiation into the Orphic Mysteries.

Thus began the history of Western esotericism.” (14)

THE ORIGINS OF THE ORPHIC MYSTERIES AND THE LEGEND OF ORPHEUS

Though the exact origins of the Orphic Mysteries remain shrouded in myth and speculation, they exerted a profound influence on the religious and cultural fabric of ancient Greece. It is within the mythical and historical narrative of Orpheus that the true foundations of the Orphic Mysteries lie.

The Orphic Mysteries find their roots in Orpheus, a figure who has been the subject of debate on whether he was a mythical or historical character. Regardless, he held great reverence as a poet, musician, and prophet that earned him the status of a divine patron.

What is certain is that Orpheus left an indelible mark on Greek, Cretan, and Freemasonic history, and his influence has persisted throughout the past 2,500 years or even longer in both classical and modern literature.

As you will see, his teachings and mythical biography served as the foundation for several initiatory cults centered around philosophy and esotericism with themes of death, rebirth, and the salvation of the soul. They provided spiritual guidance and enlightenment to their followers, drawing inspiration from the legendary figure of Orpheus.

The Orphic cosmogony presented a unique worldview, diverging from traditional Greek religious beliefs. Central to their philosophy was the concept of the soul’s transmigration, emphasizing the eternal nature of the soul and its journey through various reincarnations.

Rituals often included ceremonies of purification, symbolic sacrifices, and the consumption of ritualistic meals or drinks, such as the famous Orphic eggs and honey. This belief system offered hope for liberation from the cycle of birth and death, with the ultimate goal being the union of the soul with the divine.

His father, in various versions, is said to be Oeagrus, a Thracian king, or Apollo, the Greek god associated with music, poetry, and prophecy. He was believed to be the son of Apollo, the god of music and arts and the son of a Muse, most commonly identified as Calliope, the Muse of epic poetry. It is within the context of this divine lineage that Orpheus’s extraordinary musical abilities are often depicted. (15)

The myth of Orpheus extends beyond his musical prowess, encompassing his remarkable adventures in the underworld, his ill-fated love for Eurydice, and his role as a divine guide. The story of Orpheus and his descent into Hades to retrieve his beloved wife Eurydice serves as a profound metaphor for the power of music and the human longing for connection and redemption.

In one ancient account, it is recounted that Orpheus possessed a magical lyre, an instrument whose melodies had the power to sway the hearts of gods, animals, and even inanimate objects. The mythological aspect here lies in the notion that music, with its enchanting harmony, could transcend the boundaries of mortal existence and touch the realm of the divine

THE ORPHIC HYMNS

The most well-known text associated with Orpheus are The Orphic Hymns, which holds significant prominence in contemporary Hellenic religious worship. It was called the Orphic Kozmogonía (Cosmogony) and Thæogonía, which exist only in fragments that are scattered among the works of various ancient authors.

The earliest known mention of Orpheus is attributed to Ívykos, a poet from the sixth century BCE. Although only a small fragment remains from Ívykos’ work, it includes the phrase “famous Orphéus.” (16)

This indicates that even during that time, Orpheus had already achieved a considerable level of fame.

One such mention can be found in Plato’s Eighth Book of Laws, where the existence of Orphic hymns is alluded to. Plato, in his dialogue “Laws,” discusses various religious and philosophical matters, including the role of music and hymns in society where he explains the significance of hymns and their potential to shape moral character. (17)

Another source that refers to these hymns is Pausanias, a Greek traveler and geographer from the 2nd century AD.

Pausanias, in his work “Description of Greece” describes Orpheus as a Thracian figure who was depicted on Mount Helicon, accompanied by ΤΕΛΕΤΗ (initiation or religion), while being surrounded by representations of wild beasts, some made of marble and others of bronze. The author of the Letters on Mythology translates Pausanias’ words as follows:

“The Thracian Orpheus (says Pausanias) was represented on mount Helicon, with ΤΕΛΕΤΗ by his side, and the wild beasts of the woods and surrounded by representations of wild beasts made of marble and bronze. Pausanias also mentions that Orpheus’ hymns were known to be relatively short in length and limited in number, which suggests that they were distinctive in their brevity.(18)

According to Pausanías, he exceeded his predecessors by uncovering the divine mysteries, which ultimately led to his demise. He wrote;

“In my view Orpheus outdid his predecessors in beautiful verse, and obtained great power because people believed he discovered divine Mysteries, rites to purify wicked actions, cures for diseases, defenses against the curses of heaven. They say that the Thracian women plotted Orpheus’ death because he attracted their men to follow him in his wanderings, but because of the men they were frightened to do it;

But when they were full of wine they carried the thing through, and, ever since, the men have had the tradition of marching drunk to battle. There are some who say Orpheus died thunderblasted by the God, because of the stories he made public in the Mysteries, which men had never heard before.”

This account by Pausanías draws parallels to the Greek mythological tale of Prometheus, who suffered punishment at the hands of Zeus for divulging secrets to humanity. As punishment, Prometheus was sentenced to endure having his liver perpetually consumed by an eagle.

In Greek mythology, Prometheus, a titan, defied the gods by giving fire, a symbol of knowledge and civilization, to humanity. Zeus, angered by Prometheus’ audacity, devised a punishment to match the severity of the offense. Prometheus was bound to a rock, where an eagle would perpetually devour his liver, which regenerated daily. This cycle of torment continued until Hercules eventually freed Prometheus.

Socrates’ teachings and methods of questioning challenged the traditional beliefs and societal norms of his time. He encouraged critical thinking and the pursuit of wisdom, which sometimes involved questioning the authority of the gods and established dogmas. Plato, one of Socrates’ most prominent students, also faced accusations of divulging secret mysteries and was subjected to suspicion and scrutiny.

Socrates’ trial and subsequent death are documented by Plato in works such as “Apology” and “Phaedo.” The charges against Plato himself are mentioned in Aristophanes’ comedy “The Clouds.”

Furthermore, it finds resonance with the factual account of Socrates, who faced capital punishment at the hands of the Athenian government, and his student Plato, who also encountered accusations of revealing concealed mysteries. Then later came the Masonic myth of Hiram Abiff who on “the contrary” was killed by three fellow craftsmen known as ruffians for not revealing the mysteries and instead valuing the sacredness and secrecy of the knowledge.

According to Damáskios (Damascius, Δαμάσκιος), a Neoplatonic philosopher who lived until sometime after 538 CE, there are three significant Orphic theogonies discussed in his book on first principles, called “ἀπορίαι καὶ λύσεις περὶ τῶν πρώτων ἀρχῶν” (aporiai kai luseis peri ton prōtōn archōn). He was a leading figure in the Neoplatonic school of thought, and his writings have preserved valuable insights into ancient philosophical and religious traditions, including those of Orphismós.

In his work, Damáskios mentions a text called “The Sacred Logos in Twenty-Four Rhapsodies” (Ιερός Λόγος σε 24 Ραψωδίες). The term “rhapsodies” refers to specific sections within the text, organized similarly to the structure of the Iliad (Ἰλιάς) or the Odyssey (Ὀδύσσεια), both of which are divided into twenty-four parts or books referred to as rhapsodies.

This particular text was regarded as the established or “orthodox” theogony of Orphismós (Orphism, Ορφισμός).(19)

THE CONNECTION OF THE ORPHIC MYSTERIES TO THE ANCIENT PHILOSOPHERS AND MYSTERY SCHOOLS

Clement of Alexandria wrote extensively on various philosophical and religious topics, and he drew upon a range of sources, including Orphic literature. He said that both Orpheus and Plato derived their knowledge of the one Living and True God from the Mosaic writings, and cites these lines from one of the Orphic hymns: “One is perfect in Himself, and all things are born of One; Him no one of mortals has seen, but He sees all.”(20)

Clement’s works, such as “Exhortation to the Greeks” and “Stromateis,” contain references to the Orphic myth and shed light on its influence within the broader cultural and intellectual milieu of the time.

The 19th century German philologist and historian of Greco-Roman religions, Albrecht Dieterich (1893) argued in his influential work on Greek and Christian apocalyptic religions that Plato reproduced an authentic Orphic eschatology, a viewpoint supported more recently by Peter Kingsley (1996). (21)

Recent archeological discoveries including the Gold Tablets, the Derveni Papyrus, the Gûrob Papyrus, and an Olbian bone tablet, have significantly reshaped our understanding of Orphism and ignited a lively debate among scholars. These artifacts, considered to be among the earliest remnants associated with the Orphic tradition, have provided valuable insights into ancient religious and philosophical practices.

The Gold Tablets, for instance, were unearthed in various locations such as Thessaly and Crete, and they contain inscriptions written in ancient Greek. These tablets are believed to have been buried with the deceased, serving as guides to the afterlife according to Orphic beliefs. They offer detailed instructions and rituals aimed at securing a favorable journey for the soul. (22)

Another notable discovery, the Derveni Papyrus, was found in 1962 in Derveni, near Thessaloniki, Greece. Although not exclusively dedicated to Orphism, this ancient manuscript contains a philosophical treatise with strong connections to Orphic doctrines. It explores topics such as cosmogony, religious rituals, and the nature of the gods, providing valuable insights into the philosophical and religious landscape of the time. (23)

The Gûrob Papyrus, discovered in the late 19th century in Gûrob, Egypt, presents a collection of magical spells and religious hymns associated with Orphic practices. This papyrus has played a crucial role in unraveling the mystical aspects of Orphism, shedding light on the rituals and beliefs related to the Orphic mysteries. (24)

Additionally, the Olbian bone tablet, found in Olbia, a Greek colony on the northern coast of the Black Sea, provides yet another fascinating glimpse into the early expressions of Orphic traditions. This small bone fragment contains an inscription believed to be an invocation to the deity Dionysus, emphasizing the significance of Dionysiac elements within the Orphic cult. (25)

PYTHAGORAS

In examining the teachings of Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, it is quite evident that Orpheus and the religious and philosophical system known as Ophism had a profound influence on thier own ideas. They were well known just like Orpheus for their contributions to mathematics, music, philosophy, and mysticism.

Like is found in Ophism, Pythagoras embraced the Orphic belief in the soul’s transmigration, asserting that the soul is eternal and undergoes a cyclical process of rebirth. He regarded the body as a temporary vessel for the immortal soul, emphasizing the importance of moral and intellectual development to liberate the soul from the cycle of reincarnation.

According to 19th century British author and neo-Platonist classicist, Thomas Taylor wrote;

“In the former part of this Dissertation, we asserted that we should derive all our information concerning the Orphic theology, from the writings of the Platonists; not indeed without reason. For this sublime theology descended from Orpheus to Pythagoras, and from Pythagoras to Plato; as the following testimonies evince.

“Timæus (says Proclus) being a Pythagorean, follows the Pythagoric principles, and these are the Orphic traditions; for what Orpheus delivered mystically in secret discourses, these Pythagoras learned when he was initiated by Aglaophemus in the Orphic mysteries.” Syrianus too makes the Orphic and Pythagoric principles to be one and the same; and, according to Suidas, the same Syrianus composed a book, entitled the Harmony of Orpheus, Pythagoras and Plato.

The neoplatonic philosopher, Proclus of Athens wrote: “The whole theology of the Greeks is the child of Orphic mystagogy; Pythagoras being first taught the ‘orgies’ of the gods ‘ orgies’ signifying ‘ burstings forth, or’emanations,’ from opyaw] by Aglaophemus, and next Plato receiving the perfect science concerning such things from the Pythagorean and Orphic writings” (26)

PLATO

The study of the origins of Plato’s ontology and eschatology has intrigued many scholars since the 19th century and even further. However, when one examines Plato’s own words and many of his teachings, we find elements of Orphism throughout his work.

The 19th-century British philosopher and author, Alfred Edward Taylor (A. E. Taylor) believed that Plato, Socrates, and Pythagoras were all voluntary initiates of the Orphic mysteries and that it was an international religion. A. E. Taylor explains:

“The Socrates of the Platonic dialogues frequently refers to the dogmas of the Orphic religion as supporting his own convictions about the immortality of the soul and the importance of the life to come, and the details of the imaginative myths which he relates about Heaven and Hell in the Gorgias, Phaedo, Republic, are notoriously Orphic.

Plato, too, as we see from allusions in the Laws, regarded ancient sayings, which plainly mean the Orphic doctrines, as fables with a kernel of imperishable religious truth; but we see also from the unsparing attack on immoral mythology and religion in the second book of the Republic, which is aimed much more at Orpheus than at Homer,

Plato’s perspective on ancient sayings, particularly the Orphic doctrines, was complex. On one hand, he acknowledged that these sayings contained a core of timeless religious truth, often shrouded in the form of fables. References in his work “Laws” suggest that Plato saw value in these ancient teachings.

However, in his influential work “Republic,” Plato launched a scathing attack on immoral mythology and religious practices, primarily targeting Orpheus more than Homer. This indicates that Plato believed Orphism had undergone a decline by the time of his birth, degenerating into its followers engaging in the vulgar commercial trafficking in ‘pardons’ and ‘indulgences.’

To better understand the context of the conversation described in Plato’s Republic, we must imagine it taking place during Plato’s early childhood or even earlier. This is because his older brother, Adimantus, who appears as a young man in the dialogue, was already old enough to act as a guardian for Plato in 399.

We learn about this from Apology 34a, where Socrates refers to Adimantus as a relative who could provide an authoritative opinion on the impact of Socrates’ own society on Plato. Therefore, it is unlikely that contemporary Orphism at the time that he criticized had influenced either Plato or Socrates negatively in this regard.

Pindar’s greatest Orphic odes, however, belong to the years just before Socrates’ birth, and this suggests the probability that Socrates really had been initiated in the Orphic religion in childhood and was permanently impressed by it. It must be remembered that the Orphic religion was not that of any political community.

It was recruited, like a modern church, by voluntary initiation in its sacraments, and was ‘international.’

The original Pythagoreans merged a religion centered around the belief in an immortal soul with their scientific pursuits. This aspect, if it is indeed true, helps explain the enduring connection between Socrates and the Pythagoreans from Thebes and Phlius.

It also sheds light on Plato’s evident concern in the Euthyphro dialogue to highlight the contrast between Socrates’ piety and the peculiar beliefs of the sect follower Euthyphro. Additionally, it accounts for the existence of Aeschines’ dialogue Telauges, in which Socrates engages with an eccentric devotee who possesses dirty habits, and seemingly criticizes his way of life. (27)

According to the 20th century historian and author, W.K.C. Guthrie, he suggested that Plato simply “supplemented” Orphic religion.

Guthrie believed that Orpheus was the source of the Orphic Mysteries, a system of personal progress or evolution leading to the deification of the soul. Orpheus is known as the originator of all the Mysteries, teachings which are held with a certain degree of secrecy.

He wrote;

“As founder of Mystery-Religions, Orpheus was the first to reveal to men the meaning of rites of initiation (teletai). We read of this in both Plato and Aristophanes.”

…the existence of a sacred literature ascribed to Orpheus, evidence is not lacking to show that this was in being in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, and moreover that it was believed in those centuries to be of great antiquity.” (28)

Auguste Diès, a renowned scholar of Plato’s life and works, acknowledged the influence of Orphic thought on Plato’s philosophy while also recognizing the originality of Plato’s ideas. Diès argued that Plato transposed the religious and initiatory doctrines of Orphism into the pursuit of philosophical perfection. (29)

This perspective has been inherited by scholar, Alberto Bernabé, who further developed the theory of “transposition,” suggesting that Plato replaced the Orphic life with the philosophic life, emphasizing moral obligations and philosophical perfection instead of initiatory rights and purifications. (30)

Giovanni Reale, a historian of philosophy, emphasized the importance of Orphism in understanding not only Plato but also other influential philosophers such as Pythagoras, Heraclitus, and Empedocles. According to Reale, Orphism played a crucial role in shaping their philosophical ideas. (31)

Plato’s Orphica plays a significant role in the collection known as the Orphicorum Fragmenta, which is a compilation of ancient texts that provide insights into Orphism, an esoteric religious tradition attributed to the mythical figure Orpheus.

In Plato’s dialogue “Phaedrus,” he presents a myth inspired by the Orphic tradition, where the soul is depicted as a divine charioteer seeking to ascend to the realm of eternal truths. In the dialogue, Plato discusses the concept of the soul’s journey through cycles of incarnation and judgment. (32)

This idea bears a resemblance to both Egyptian and Orphic teachings regarding the transmigration of souls and his belief in the soul’s immortality and its longing for union with the transcendental realm. (33)

Plato also alludes to the teachings that resonate with Gnosticism with the Orphic belief that the soul is a prisoner to the sōma “body/tomb”. By exploring the etymology of the word “sōma,” Plato suggests that the physical body serves as both a vessel for the soul and a confining tomb.

This dialogue provides insights into the notion of the soul’s entrapment within the material realm, which underscores the influence of Orphic or Gnostic thought on later philosophical and religious movements, as well as the broader dialogue between ancient wisdom traditions, including Christianity.

The concept of “soma-sema,” meaning “body-prison,” is one of the well-known phrases associated with the teachings of Pythagoras and Plato in ancient Greece. This phrase reveals the ancient belief and Gnostic concept that the soul is trapped within the body and acts as a sort of metaphysical prison for our true spirit.

Plato’s dialogue Cratylus (400c) is one of the primary sources where Socrates mentions the Orphics as probable inventors of this idea.

However, when examining the Orphic mystery cults in ancient Greece may provide some insights, but the fundamental teachings of “soma-sema” can be found in the mysticism of Pharaonic Egypt, predating both Pythagoras and Plato.(34)

The phrase “soma-sema” serves as a reminder of the intricate interplay between different civilizations and the evolution of ideas over time. By understanding the historical context and sources, we can appreciate the cross-cultural exchange between the East and West and the complex origins of philosophical concepts.

The dialogue also explores the nature of language, names, and their connection to reality. Socrates speculates that the Orphics, with their theogonic myth, played a significant role in shaping the understanding of language and its relationship to divine entities.

Moreover, Socrates makes references to Orphic beliefs in other dialogues as well. In Phaedrus (250c), Socrates discusses the immortality of the soul and draws upon Orphic teachings to support his arguments. Similarly, in Gorgias (493a), Socrates refers to the Orphics when discussing the nature of rhetoric and its moral implications.

While it is commonly associated with Greek philosophy and Gnosticism, its origins can be traced back to the Egyptian mysteries in which Pythagoras and Plato were initiated.

One of the most well-known stories involving Orpheus is his descent into the realm of Hades, the underworld, in a desperate attempt to bring his deceased wife, Eurydice, back to the realm of the living. This tale of love and devotion can also be found in Plato’s Symposium (179d) where we find Orpheus’s journey to Hades, showcasing his determination and willingness to confront death itself.

However, it is important to note that Plato’s portrayal of Orpheus in his writings is marked by a mixture of admiration and criticism. Plato also expresses reservations about certain aspects of Orphic beliefs and practices.

In Plato’s famous work, “The Republic,” he presents a dialogue where he criticizes the priests associated with the Orphic tradition. These priests engaged in the commercialization of knowledge, tempting people with the promise of enlightenment through the sale of numerous Orphic books.

In this section, Plato engages in a discussion on poetry, a form of art often associated with the Orphic tradition. He raises concerns about the influence of poets and their potential to mislead and corrupt the minds of citizens.

Plato argues that poets, including these traveling priests of Orpheus, often rely on emotional appeal and rhetoric to manipulate and sway their audience without providing genuine knowledge or understanding.

By targeting the Orphic priests specifically, Plato addresses a broader issue of charlatans who exploit people’s thirst for wisdom, undermining the pursuit of genuine knowledge. His skepticism towards these priests and their supposed authority over esoteric teachings reflects his philosophical commitment to seeking truth through reason rather than relying on external authorities.

This ancient phenomenon of both mental and spiritual exploitation for monetary gain is nothing new and can be found throughout the history of all religions, secret societies and even atheist organizations.

OTHER PHILOSOPHERS

Heraclitus, a prominent pre-Socratic philosopher, also exhibited traces of Orphic influence in his philosophical musings. His concept of the “Logos” as the universal principle of order and change bears similarities to Orphic notions of a divine organizing force. Heraclitus’ emphasis on the ephemeral nature of reality and the cyclical nature of existence resonates with the Orphic belief in the soul’s journey through multiple reincarnations.

Philostratus presents the idea that when we examine the conflicts among the Gods depicted in the Iliad, we should bear in mind that the poet engaged in a philosophical approach influenced by Orphism. (35)

This perspective is supported by Plutarch, who explains that the earliest philosophers concealed their teachings through the use of fables and symbols, specifically citing the Orphic writings and Phrygian myths. He further argues that ancient natural science, both among the Greeks and foreigners, was largely veiled within these myths—a cryptic and mysterious theology that held a hidden and enigmatic meaning. Plutarch says evidence for this notion can be found in the Orphic poems as well as the treatises of the Egyptians and Phrygians. (36)

CONCLUSION:

The Orphic tradition and the mythical figure of Orpheus have left an indelible mark on Greek philosophy, permeating the works of renowned thinkers throughout history. Pythagoras, Plato, Empedocles, and Heraclitus are just a few examples of philosophers who integrated Orphic teachings into their philosophies.

These examples demonstrate the profound intertwining of myth and allegory in the tales surrounding Orpheus. They depict him as a figure who transcends the boundaries of mere mortal existence, embodying divine qualities and serving as a catalyst for societal and spiritual transformation.

The enduring fascination with Orpheus throughout history is a testament to the enduring power of these narratives and their impact on our understanding of this legendary figure.

Undoubtedly, Orpheus still holds a position of great significance among the prominent figures of ancient Greece and Crete. His influence and legacy have endured through the centuries, capturing the imagination and reverence of both ancient and more recent civilizations.

The Orphic teachings served as the foundation for many ancient initiatory cults centered around themes of death, rebirth, and the salvation of the soul, which provided spiritual guidance and enlightenment to its followers.

The influence of the Orphic Mysteries extended beyond the boundaries of Greece. The spread of Hellenistic culture and the subsequent rise of the Roman Empire facilitated the dissemination of Orphic ideas throughout the Mediterranean world.

SOURCES:

1. Orphism – The Oxford Classical Dictionary & Encyclopædia Britannica

2. Orpheus and Greek Religion by W. K. C. Guthrie, 1935

3. Taylor, Thomas. “The Fragments That Remain of the Lost Writings of Origen: Orphica.” (1825)

4. Diodorus Siculus – The Library of History Page 10

5. Otto Kern – Orphicorum Fragmenta

6. Pausanias. – Description of Greece, Book IX, Translated by W.H.S. Jones (1918)

7. Jung, Man and His Symbols, p. 142

8. Jung – Psychology and Religion: West and East Princeton University Press, 2014

9. Jung – Psychology and Alchemy

10. Jung – The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

11. Giuliano Di Bernardo – The Esoteric Foundation of Humanity

12. Albert Pike Morals and Dogma Chapter of Rose Croix: XVII. Knight of the East and West

13. Manly P. Hall – Newsletter March 15, 1937

14. Dr. Nicolas Laos –

15. Pindar, Pythian 4.176-177; Euripides, Alcestis 357-362

16. Pausanias’s Description of Greece: Translation – Page 481

17. Plato, “Laws,” Book VIII:

18. Pausanias’s Description of Greece – Volume 1 – Page 481b, James George Frazer · 1898

19. Damáskios (Damascius; Gr. Δαμάσκιος) I.317.15 Ruelle; summarized from THE DERVENI PAPYRUS – Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation by Gábor Betegh, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 143-144. (I.317.15 Ruelle)

20. Clement of Rome – https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf02.vi.iv.v.xii.html

21. Dieterich, A. (1893). Eine Mithrasliturgie (Vol. 1). Leipzig: Dieterich’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung

22. Gold Tablets: Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, “Myths of the Underworld Journey: Plato, Aristophanes, and the ‘Orphic’ Gold Tablets” (2004)

23. Derveni Papyrus: Richard Janko, “The Derveni Papyrus: Cosmology, Theology, and Interpretation” (2005)

24. Gûrob Papyrus: Alberto Bernabé, “Orphism and Christianity in Late Antiquity” (2010)

25. Olbian bone tablet: Fritz Graf, “Greek Mythology: An Introduction” (1993)

26. Taylor, Thomas. “The Fragments That Remain of the Lost Writings of Origen: Orphica.” (1825)

27. Socrates: The Man and His Thought by A. E. Taylor, 1933 (Chapter 2 pp. 50-52.)

28. Orpheus and Greek Religion by W. K. C. Guthrie, 1935. We are using the 1993 reprint by Princeton Univ. Press (Princeton, NJ USA), p 17

29. Diès, A. Leçons sur la philosophie de Platon. Paris: Société d’Edition “Les Belles Lettres. (1927)

30. Bernabé, A. Orphism and Christianity in Late Antiquity. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter (2011)

31. Reale, G. (1987). Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans

32. Plato Phaedrus 249

33. Plato Cratylus 400

34. Burkert, Walter. Ancient Mystery Cults. Harvard University Press (1987)

35. Philostratus’s Heroikos: Religion and Cultural Identity in the Third Century C.E.” Translated by Jennifer K. Berenson Maclean. Society of Biblical Literature (2004)

36. Plutarch, “Plutarch’s Morals: Ethical Essays.” Translated by William W. Goodwin. Little, Brown, and Company (1871)

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.