When the symbolism of this diluvian legend is unravelled, one perceives at once the real meaning of the allegory. The giant Ymir typifies the primitive rude organic matter, the blind cosmical forces, in their chaotic state, before they received the intelligent impulse of the Divine Spirit which set them into a regular motion dependent on immovable laws. The progeny of Bur are the “sons of God,” or the minor gods mentioned by Plato in the Timaeus, and who were intrusted, as he expresses it, with the creation of men; for we see them taking the mangled remains of Ymir to the Ginnunga-gap, the chaotic abyss, and employing them for the creation of our world. His blood goes to form oceans and rivers; his bones, the mountains; his teeth, the rocks and cliffs;

Page 151

his hair, the trees, etc.; while his skull forms the heavenly vault, supported by four pillars representing the four cardinal points. From the eye-brows of Ymir was created the future abode of man — Midgard.

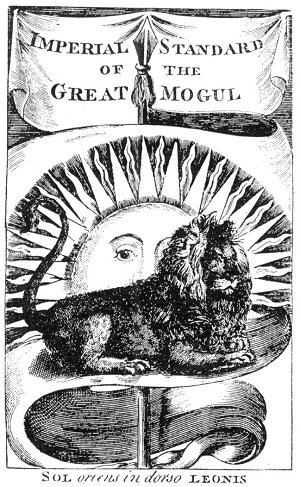

This abode (the earth), says the Edda, in order to be correctly described in all its minute particulars, must be conceived as round as a ring, or as a disk, floating in the midst of the Celestial Ocean (Ether). It is encircled by Yormungand, the gigantic Midgard or Earth Serpent, holding its tail in its mouth. This is the mundane snake, matter and spirit, combined product and emanation of Ymir, the gross rudimental matter, and of the spirit of the “sons of God,” who fashioned and created all forms. This emanation is the astral light of the Kabalists, and the as yet problematical, and hardly known, aether, or the “hypothetical agent of great elasticity” of our physicists.

How sure the ancients were of this doctrine of man’s trinitarian nature may be inferred from the same Scandinavian legend of the creation of mankind. According to the Voluspa, Odin, Honir, and Lodur, who are the progenitors of our race, found in one of their walks on the ocean-beach, two sticks floating on the waves, “powerless and without destiny.” Odin breathed in them the breath of life; Honir endowed them with soul and motion; and Lodur with beauty, speech, sight, and hearing. The man they called Askr — the ash, and the woman Embla — the alder. These first men are placed in Midgard (mid-garden, or Eden) and thus inherit, from their creators, matter or inorganic life; mind, or soul; and pure spirit; the first corresponding to that part of their organism which sprung from the remains of Ymir, the giant-matter, the second from the AEsir, or gods, the descendants of Bur, and the third from the Vanr, or the representative of pure spirit.

Another version of the Edda makes our visible universe spring from beneath the luxuriant branches of the mundane tree — the Yggdrasill, the tree with the three roots. Under the first root runs the fountain of life, Urdar; under the second is the famous well of Mimer, in which lie deeply buried Wit andWisdom. Odin, the Alfadir, asks for a draught of this water; he gets it, but finds himself obliged to pledge one of his eyes for it; the eye being in this case the symbol of the Deity revealing itself in the wisdom of its own creation; for Odin leaves it at the bottom of the deep well. The care of the mundane tree is intrusted to three maidens (the Norns or Parcae), Urdhr, Verdandi, and Skuld — or the Present, the Past, and the Future. Every morning, while fixing the term

Page 152

of human life, they draw water from the Urdar-fountain, and sprinkle with it the roots of the mundane tree, that it may live. The exhalations of the ash, Yggdrasill, condense, and falling down upon our earth call into existence and change of form every portion of the inanimate matter. This tree is the symbol of the universal Life, organic as well as inorganic; its emanations represent the spirit which vivifies every form of creation; and of its three roots, one extends to heaven, the second to the dwelling of the magicians — giants, inhabitants of the lofty mountains — and at the third, under which is the spring Hvergelmir, gnaws the monster Nidhogg, who constantly leads mankind into evil. The Thibetans have also their mundane tree, and the legend is of an untold antiquity. With them it is called Zampun. The first of its three roots also extends to heaven, to the top of the highest mountains; the second passes down to the lower region; the third remains midway, and reaches the east. The mundane tree of the Hindus is the Aswatha. Its branches are the components of the visible world; and its leaves the Mantras of the Vedas, symbols of the universe in its intellectual or moral character.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.