Who can study carefully the ancient religious and cosmogonic myths without perceiving that this striking similitude of conceptions, in their exoteric form and esoteric spirit, is the result of no mere coincidence, but manifests a concurrent design? It shows that already in those ages which are shut out from our sight by the impenetrable mist of tradition, human religious thought developed in uniform sympathy in every portion of the globe. Christians call this adoration of nature in her most concealed verities — Pantheism. But if the latter, which worships and reveals to us God in space in His only possible objective form — that of visible nature — perpetually reminds humanity of Him who created it, and a religion of theological dogmatism only serves to conceal Him the more from our sight, which is the better adapted to the needs of mankind?

Modern science insists upon the doctrine of evolution; so do human reason and the “secret doctrine,” and the idea is corroborated by the ancient legends and myths, and even by the Bible itself when it is read between the lines. We see a flower slowly developing from a bud, and the bud from its seed. But whence the latter, with all its predetermined programme of physical transformation, and its invisible, therefore spiritual forces which gradually develop its form, color, and odor? The word evolution speaks for itself. The germ of the present human race must have preexisted in the parent of this race, as the seed, in which lies hid-

Page 153

den the flower of next summer, was developed in the capsule of its parent-flower; the parent may be but slightly different, but it still differs from its future progeny. The antediluvian ancestors of the present elephant and lizard were, perhaps, the mammoth and the plesiosaurus; why should not the progenitors of our human race have been the “giants” of the Vedas, the Voluspa, and the Book of Genesis? While it is positively absurd to believe the “transformation of species” to have taken place according to some of the more materialistic views of the evolutionists, it is but natural to think that each genus, beginning with the mollusks and ending with monkey-man, has modified from its own primordial and distinctive form. Supposing that we concede that “animals have descended from at most only four or five progenitors”; and that even a la rigueur “all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form”; still no one but a stone-blind materialist, one utterly devoid of intuitiveness, can seriously expect to see “in the distant future . . . psychology based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation.” Physical man, as a product of evolution, may be left in the hands of the man of exact science. None but he can throw light upon the physical origin of the race. But, we must positively deny the materialist the same privilege as to the question of man’s psychical and spiritual evolution, for he and his highest faculties cannot be proved on any conclusive evidence to be “as much products of evolution as the humblest plant or the lowest worm.”

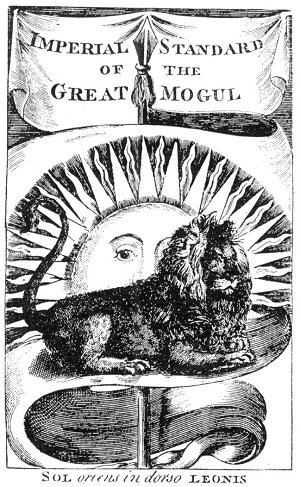

Having said so much, we will now proceed to show the evolution-hypothesis of the old Brahmans, as embodied by them in the allegory of the mundane tree. The Hindus represent their mythical tree, which they call Aswatha, in a way which differs from that of the Scandinavians. It is described by them as growing in a reversed position, the branches extending downward and the roots upward; the former typifying the external world of sense, i.e., the visible cosmical universe, and the latter the invisible world of spirit, because the roots have their genesis in the heavenly regions where, from the world’s creation, humanity has placed its invisible deity. The creative energy having originated in the primordial point, the religious symbols of every people are so many illustrations of this metaphysical hypothesis expounded by Pythagoras, Plato, and other

Page 154

philosophers. “These Chaldeans,” says Philo, “were of opinion that the Kosmos, among the things that exist, is a single point, either being itself God (Theos) or that in it is God, comprehending the soul of all the things.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.