This is still another of the many sentences by which Paul must be recognized as an initiate. For reasons fully explained, we give far more credit for genuineness to certain Epistles of the apostles, now dismissed as apocryphal, than to many suspicious portions of the Acts. And we find corroboration of this view in the Epistle of Paul to Seneca. In this message Paul styles Seneca “my respected master,” while Seneca terms the apostle simply “brother.”

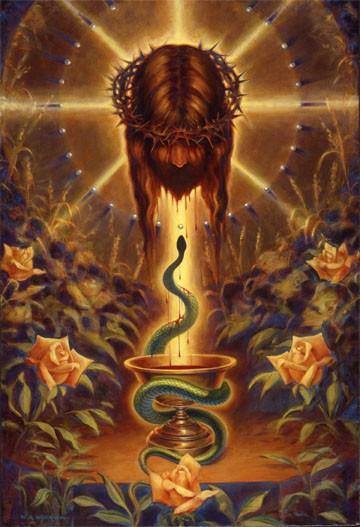

No more than the true religion of Judaic philosophy can be judged by the absurdities of the exoteric Bible, have we any right to form an opinion of Brahmanism and Buddhism by their nonsensical and sometimes disgusting popular forms. If we only search for the true essence of the philosophy of both Manu and the Kabala, we will find that Vishnu is, as well as Adam Kadmon, the expression of the universe itself; and that his incarnations are but concrete and various embodiments of the manifestations of this “Stupendous Whole.” “I am the Soul, O, Arjuna. I am the Soul which exists in the heart of all beings; and I am the beginning and the middle, and also the end of existing things,” says Vishnu to his disciple, in Bagaved-gitta (ch. x., p. 71).

“I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end. . . . I am the first and the last,” says Jesus to John (Rev. i. 6, 17).

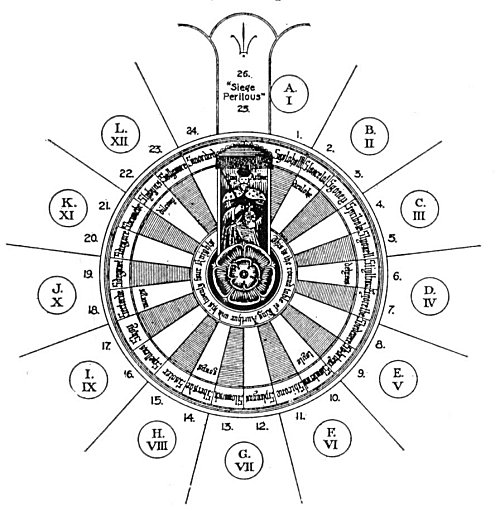

Brahma, Vishnu, and Siva are a trinity in a unity, and, like the

Page 278

Christian trinity, they are mutually convertible. In the esoteric doctrine they are one and the same manifestation of him “whose name is too sacred to be pronounced, and whose power is too majestic and infinite to be imagined.” Thus by describing the avatars of one, all others are included in the allegory, with a change of form but not of substance. It is out of such manifestations that emanated the many worlds that were, and that will emanate the one — which is to come.

Coleman, followed in it by other Orientalists, presents the seventh avatar of Vishnu in the most caricatured way. Apart from the fact that the Ramayana is one of the grandest epic poems in the world — the source and origin of Homer’s inspiration — this avatar conceals one of the most scientific problems of our modern day. The learned Brahmans of India never understood the allegory of the famous war between men, giants, and monkeys, otherwise than in the light of the transformation of species. It is our firm belief that were European academicians to seek for information from some learned native Brahmans, instead of unanimously and incontinently rejecting their authority, and were they, like Jacolliot — against whom they have nearly all arrayed themselves — to seek for light in the oldest documents scattered about the country in pagodas, they might learn strange but not useless lessons. Let any one inquire of an educated Brahman the reason for the respect shown to monkeys — the origin of which feeling is indicated in the story of the valorous feats of Hanouma, the generalissimo and faithful ally of the hero of Ramayana, and he would soon be disabused of the erroneous idea that the Hindus accord deific honors to a monkey-god. He would, perhaps, learn — were the Brahman to judge him worthy of an explanation — that the Hindu sees in the ape but what Manu desired he should: the transformation of species most directly connected with that of the human family — a bastard branch engrafted on their own stock before the final perfection of the latter. He might learn, further, that in the eyes of the

Page 279

educated “heathen” the spiritual or inner man is one thing, and his terrestrial, physical casket another. That physical nature, the great combination of physical correlations of forces ever creeping on toward perfection, has to avail herself of the material at hand; she models and remodels as she proceeds, and finishing her crowning work in man, presents him alone as a fit tabernacle for the overshadowing of the Divine spirit. But the latter circumstance does not give man the right of life and death over the animals lower than himself in the scale of nature, or the right to torture them. Quite the reverse. Besides being endowed with a soul — of which every animal, and even plant, is more or less possessed — man has his immortal rational soul, or nous, which ought to make him at least equal in magnanimity to the elephant, who treads so carefully, lest he should crush weaker creatures than himself. It is this feeling which prompts Brahman and Buddhist alike to construct hospitals for sick animals, and even insects, and to prepare refuges wherein they may finish their days. It is this same feeling, again, which causes the Jain sectarian to sacrifice one-half of his life-time to brushing away from his path the helpless, crawling insects, rather than recklessly deprive the smallest of life; and it is again from this sense of highest benevolence and charity toward the weaker, however abject the creature may be, that they honor one of the natural modifications of their own dual nature, and that later the popular belief in metempsychosis arose. No trace of the latter is to be found in the Vedas; and the true interpretation of the doctrine, discussed at length in Manu and the Buddhistic sacred books, having been confined from the first to the learned sacerdotal castes, the false and foolish popular ideas concerning it need occasion no surprise.

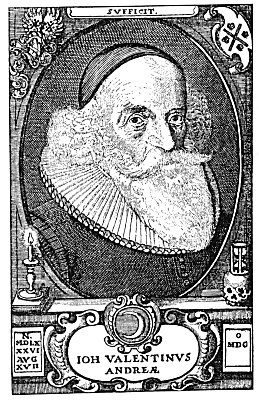

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.