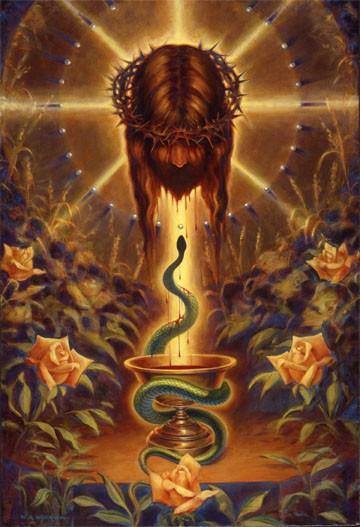

And why should they, when these contradictions are, in fact, no contradictions at all? It ill behooves us to speak of contradictions in other peoples’ religions, when those of our own have bred, besides the three great conflicting bodies of Romanism, Protestantism, and the Eastern Church, a thousand and one most curious smaller sects. However it may be, we have here a term applied to one and the same thing by the Buddhist holy “mendicants” and Paul, the Apostle. When the latter says: “If so be that I might attain the resurrection from among the dead [the Nirvana], not as though I had already attained, or were already perfect” (initiated), he uses an expression common among the initiated Buddhists. When a Buddhist ascetic has reached the “fourth degree,” he is considered a rahat. He produces every kind of phenomena by the

Page 288

sole power of his freed spirit. A rahat, say the Buddhists, is one who has acquired the power of flying in the air, becoming invisible, commanding the elements, and working all manner of wonders, commonly, and as erroneously, called meipo (miracles). He is a perfect man, a demi-god. A god he will become when he reaches Nirvana; for, like the initiates of both Testaments, the worshippers of Buddha know that they “are gods.”

“Genuine Buddhism, overleaping the barrier between finite and infinite mind, urges its followers to aspire, by their own efforts, to that divine perfectibility of which it teaches that man is capable, and by attaining which man becomes a god,” says Brian Houghton Hodgson.

Dreary and sad were the ways, and blood-covered the tortuous paths by which the world of the Christians was driven to embrace the Irenaean and Eusebian Christianity. And yet, unless we accept the views of the ancient Pagans, what claim has our generation to having solved any of the mysteries of the “kingdom of heaven”? What more does the most pious and learned of Christians know of the future destiny and progress of our immortal spirits than the heathen philosopher of old, or the modern “Pagan” beyond the Himalaya? Can he even boast that he knows as much, although he works in the full blaze of “divine” revelation? We have seen a Buddhist holding to the religion of his fathers, both in theory and practice; and, however blind may be his faith, however absurd his notions on some particular doctrinal points, later engraftings of an ambitious clergy, yet in practical works his Buddhism is far more Christ-like in deed and spirit than the average life of our Christian priests and ministers. The fact alone that his religion commands him to “honor his own faith, but never slander that of other people,” is sufficient. It places the Buddhist lama immeasurably higher than any priest or clergyman who deems it his sacred duty to curse the “heathen” to his face, and sentence him and his religion to “eternal damnation.” Christianity becomes every day more a religion of pure emotionalism. The doctrine of Buddha is entirely based on practical works. A general love of all beings, human and animal, is its nucleus. A man who knows that unless he toils for himself he has to starve, and understands that he has no scapegoat to carry the burden of his iniquities for him, is ten times as likely to become a better man than one who is taught that murder, theft, and profligacy can be washed in one instant as white as snow, if he but believes in a God who, to borrow an expression of Volney, “once took food upon earth, and is now himself the food of his people.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.